BAR HARBOR—A leak from one of MDI High School’s three wastewater lagoons this April continues to be a mystery, but one that School Superintendent Mike Zboray, Principal Matt Haney and others are determined to solve, the MDI High School Board of Trustees learned during its meeting Monday evening.

The questions include how much has leaked; how is it leaking; and how can they fix the problem of not fully treated wastewater entering the environment.

The meeting was mostly discussion of last week’s public information session about the status of the high school’s wastewater treatment plant and the forever chemicals (PFAS) that have been found in the soil and the school’s water, including the drinking water. The drinking water is now filtered. There will be another public information session in late August.

PFAS are also in the lagoons where the school’s wastewater is treated.

There was no verbal public comment at the Monday meeting, but there was a letter in the board members’ packets from David MacDonald and Caroline Pryor, neighbors to the high school who found forever chemicals in their well water.

In that letter, they wrote,

“If poisoning your own well and very likely the wells of neighbors does not represent a crisis, what does? There should not have to be a “massive breach” of the ponds to consider this a crisis and priority. A steady leak into the groundwater over the last several decades is equally disturbing and maybe more damaging to public health.

“MDI High School’s well water has elevated and unsafe PFAS levels before going through the new filter system. The likelihood that this contamination is caused by the school’s own wastewater system - either through leakage or spraying or some combination - is high, although the disclosure in March that the “upper field” was constructed of municipal sludge adds another potential source of PFAS contamination.

“It is very disturbing to neighbors and the community that PFAS contamination may be exacerbated every day by: 1.) leaking septic ponds and 2.) an antiquated spraying system.”

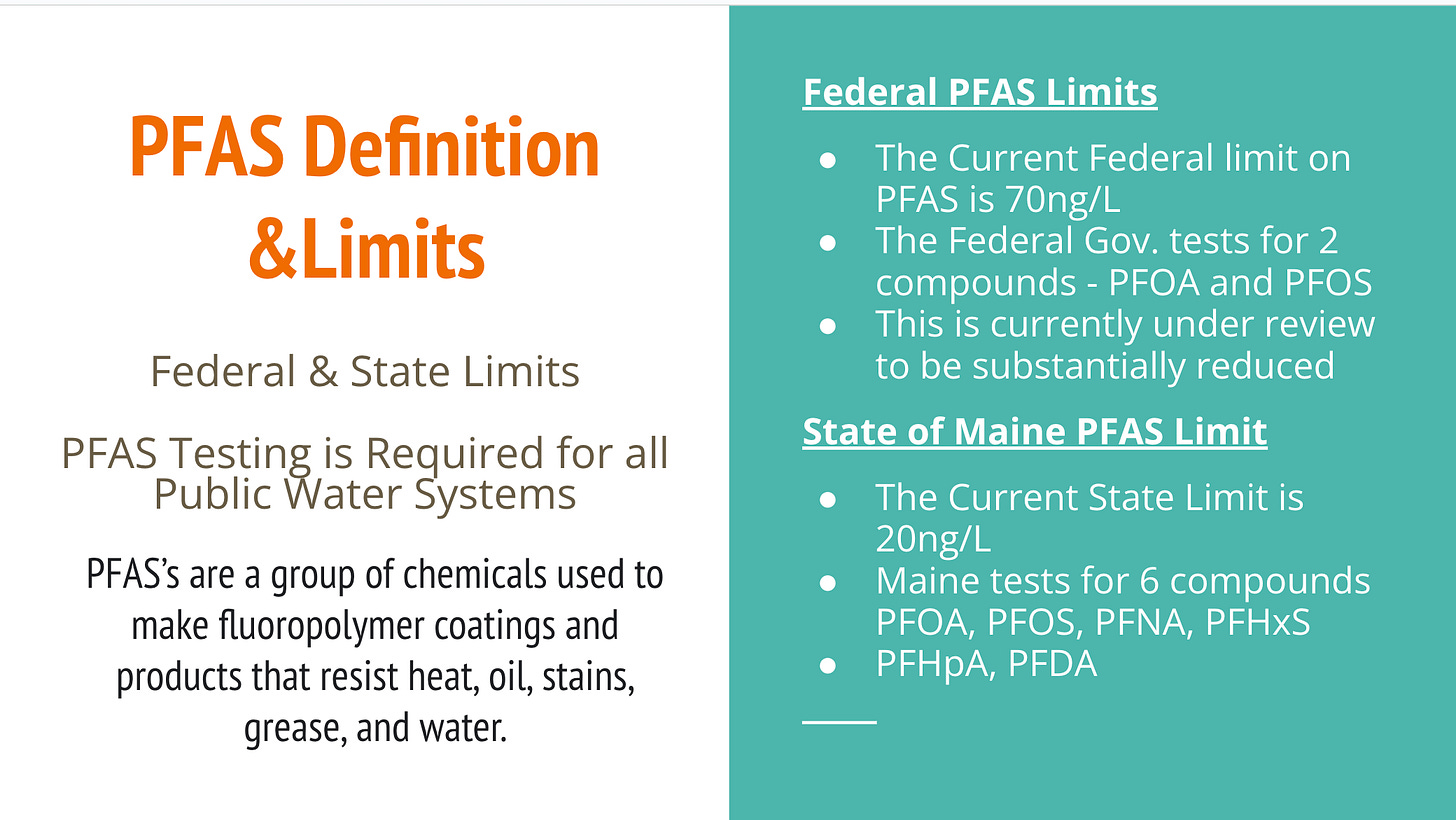

In July, the school’s drinking water was tested for PFAS, which are per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, often called “forever chemicals.” Maine tests for PFOA, PFOS, PFNA, PFHxS, PFHpA, and PFDA. These same chemicals were found in MacDonald and Pryor’s wells. Now, other neighbors are testing, too. The water can be filtered to what the state government considers safe via a $4,000-5,000 filtration system. These chemicals may have health negative health consequences according to the EPA.

The school’s process for treating the wastewater is a seasonal spray system where the sanitized water is sprayed off between April 15 and November 15 or December 1. The affluent that goes into the field is tested periodically, John Pond of Haley-Ward Engineering and Environmental Consulting said at an earlier meeting. And throughout the year some of the three lagoons that hold the water are meant to treat that water and some are meant to simply store it. The license for the system is renewed every five years. The last renewal was 2020. The DEP has not requested that it be shut down, but it needs some work, Pond had said, because it is leaking. That leak could possibly be occurring in a crack in the ledge in one of the lagoons.

There will be more testing of the soil and three monitoring wells, Zboray told board members on Monday, and they’ve isolated seven testing sites, including surface water at the high school. Two sites have already been sampled, but the results haven’t returned. One of those collections was for the water that leaves the high school.

Board member Keri Hayes said that since the state has been testing one of the monitoring wells (well #2) for years, it would be interesting to see if the PFAS levels have changed. She also asked to have the soil tested in the area where sanitized wastewater is sprayed onto fields.

Incoming board member Chad Terry asked about the May Department of Environmental Protection report, which was included in the Monday board packet and if it had been received prior to last week’s public information meeting. It had been. Terry said that the report was a big piece of information that should have been provided to the public.

DEP inspectors visited the site on April 19 for a routine inspection following the loss of wastewater.

But how much water left the lagoon is still in question according to representatives from Haley-Ward and administrators at that Monday meeting. Another question is where the leaked water went.

DEP inspector Michael Louglin’s report mentions not finding upwellings on the lagoons’ perimeters, but that there were areas of standing water, many with red residue that comes from iron. One bit of standing water “was clear and there was no grey slime growing in the area.”

The underdrain had about 5 to 10 gallons flowing in it per minute (7,000 to 14,000 gallons a day). This water had no odor and was clear. The E.coli was less than 1/100/ml and the fecal coliform was 3/100 ml.

“There was no clear indication where the 300,000 gallons of wastewater from Lagoon 2 went. The only location the wastewater could go is downhill to the wetland adjacent to the lagoons,” he wrote.

His report also reads:

The state said that the school needs to perform daily monitoring of the lagoon banks “looking for a loss of water from the lagoons until the lagoons are empty.” Those observations must be recorded and submitted to the state each month.

The middle lagoon was initially believed to be leaking significantly, about 100,000 gallons in a couple of days. “It was an all-hands-on-deck emergency,” Haney told the audience at the public information session. There are ten million gallons of wastewater in the middle lagoon or pond.

There was construction going on at the third lagoon when the second began to leak, which compounded the problem. The school began the expensive process of trucking the water to Ellsworth. The PFAS in the water, he said, was at a level that allowed Ellsworth to take it.

However, during an early May meeting, it was determined that it was “highly unlikely” that the lagoon was leaking at that rate. This was good news because, according to Pond, it wasn’t sustainable to continue to haul the water offsite because of the cost and the sludge in the lagoon. Landfills are already currently overwhelmed with sludge from wastewater facilities, he said.

A May 10 letter from Haley-Ward stipulates the company’s goals for reviewing the existing wastewater treatment system, the state license, and the design of the system. It will then present possible improvements, which could include updating the current system, creating a subsurface wastewater disposal system, and an “additional alternative.” This analysis costs $18,000. The final report would be done June 15.

During the meeting, Chair Robert Jordan suggested a wastewater subcommittee. This was rejected as an unnecessary step of complication. Hayes suggested an advisory board of local scientists and engineers like Dr. Jane Disney who has already volunteered to help neighbors with their well tests. This was rejected as being too early in the process.

MacDonald and Pryor’s letter is below.

For our story last week, which delves more into PFAS and neighbors and testing and health ramifications, click here.

Agenda and link to public comment and other files.

https://haleyward.com/leadership-team/