Knowing It's Coming

Oceanarium & others prepare for coastal sea levels rise and the flooding it brings by using history, stencils & science

BAR HARBOR—Jeff Cumming has a bit of a cough still, recovering from a cold that’s lingered, caught from one of his three daughters, but the tall, lanky man’s face still lights up when he thinks of what he’s done: His family’s nonprofit has purchased a 19-acre property that has a flooding problem and he’s determined that he’s not just going to go with that flooding; he’s going to use it to help educate people.

It seems wild, maybe a little risky? But Cumming might be ahead of his time.

He’s not just ahead of his time because he’s dealing with sea rise at his low-lying Oceanarium, a nonprofit museum that just opened last month, a property that’s surrounded by tidal marsh. He’s also ahead of his time because he’s working collaboratively with other groups and agencies to understand what’s happening at the Oceanarium, to educate others about what happens on their properties, and to actively empower Mount Desert Island to come together and think about what rising sea levels have meant to this community and will mean for it in the future.

When Cumming initially visited the property located adjacent to Jones Marsh at the head of the island, he knew flooding was a possibility.

“When we first even looked at the property, there was water in the parking lot,” he said. “It was obvious.”

They bought it anyway. His three girls loved the trails, the site. He couldn’t stand driving by year after year and seeing the beautiful property vacant.

During the December 2022 storm just before Christmas, two of the buildings flooded. One filled with eight to nine inches of water. About 12 inches of water infiltrated the other.

The question became, he said, “how do we deal with it and how do we make use of it?”

Since he’s also a carpenter, and since the nonprofit can’t currently afford to lift the buildings and can’t afford flood panels, they’re currently being creative and using construction knowledge to plan to deal with future flooding events. That creativity includes water-resistant insulation, spraying things down with vinegar to prevent mold, and creating easy access in the lower walls to deal with wet insulation when flooding happens. And he’s pretty sure it will. Again and again.

Because of where the Oceanarium is situated in salty tidal marshes, “the entire campus is a sea-level-rise exhibit,” Cumming said. “We fortunately found kind people who are working on the same thing.”

That thing is trying to deal with and understand how rising seas will impact the coast line, animals, infrastructure and people of Mount Desert Island. Those kind people he mentions are from the Mount Desert Island Historical Society, Acadia National Park, Schoodic Institute, the Mount Desert Island Biological Laboratory, College of the Atlantic, A Climate to Thrive, and local high school students and their teacher, too.

Those kind people, it turns out, are everywhere.

KING TIDES AND STORM TIDES AND MDI HIGH SCHOOL

This past fall, the Mount Desert Island Historical Society joined MDI High School’s Ruth Poland’s environmental science students to focus on how climate change has effected Mount Desert Island. They went into the archives, gathering baseline data.

In October they went out into the field, measuring, taking photographs, trying to see how king tides impact coastal areas now and how those areas, like at the Oceanarium and Seawall, will be impacted by the predicted sea rise caused by climate change.

According to the National Ocean Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), “a king tide is a non-scientific term people often use to describe exceptionally high tides. Tides are long-period waves that roll around the planet as the ocean is "pulled" back and forth by the gravitational pull of the moon and the sun as these bodies interact with the Earth in their monthly and yearly orbits. Higher than normal tides typically occur during a new or full moon and when the Moon is at its perigee, or during specific seasons around the country.”

It is basically, the highest tide or tides of the year. The king tides also give people a preview of where the future regular average day’s high tide will be. They show a community where sea level rise is going to make an impact. They show a community where it’s going to have to try to tweak or change infrastructure to deal with that impact. They show a community what its future might look like.

You can’t drive over Route 3 if parts of it are flooded.

You probably don’t want to build housing in a place that’s going to be underwater.

You probably want to shore up infrastructure or find ways to mitigate houses and businesses in flood-risk areas.

As the EPA says, “Sea level rise will make today’s king tides become the future’s everyday tides.”

According to the Schoodic Institute, “higher sea levels mean that storm waves and flooding are also higher. The worst case scenario of a storm arriving at the same time as a king tide occurred December 2022. A three-foot surge in water levels provided a glimpse of average sea level rises in the future.”

While researching, those Mount Desert Island High School students also realized how close the predicted sea level rise is to the infrastructure of Mount Desert Island.

Mount Desert Island Historical Society’s Executive Director Raney Bench pointed this same worry out at the Oceanarium where Jones Marsh is on one side of Route 3 and the Oceanarium, tidal marshes, and bay are on the other. The road bisects the natural draining system, two small culverts beneath it.

“It’s an artificial barrier to the water shed,” she said.

And when the water rises? Multiple island roads will be impacted.

A February 2022 NYT article by Henry Fountain quotes Rick Spinrad, the administrator of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration as saying, “What we’re reporting out is historic. The United States is expected to experience as much sea level rise in the next 30 years as we saw over the span of the last century.”

When they were out with the students, Bench and Poland asked them to visualize what would happen if a storm surge and a king’s tide occurred simultaneously.

“They said, ‘When will that ever happen?’ And then—it happened in December,” Bench said.

That December 2022 storm swept away one of the Oceanarium’s observation decks. Workers waited until another high tide, tied the platform to a kayak, and pulled it across the water, putting it back in place. That storm coincided with another king tide.

On August 3, they’ll be yet another king tide, which Bench says is an opportunity to get out and take photos with reference points so people can see what the future holds. She hopes to add that information to an interactive digital map created by Catherine Schmitt, the Schoodic Institute’s science and communications specialist.

The class and fieldwork made some students realize that sea level change isn’t just a future scenario.

Poland said her students had a wonderful experience.

“Seeing historic documents of flooding events, exploring maps of high tides and comparing them with infrastructure, and then going on a tour of the island during a King Tide made everything feel so much more 'real' to them,” Poland said. “Students got a really visceral feel for what the future might hold for our island in just that one aspect of how climate change will affect our lives.”

“It’s actually happening now,” one student said. “I live right on the coast and (it showed me) how actually, really soon, my house could be somewhat underwater or my lawn maybe.” It helped her see how fast the sea is rising.

Another one felt hopeful. By knowing what was going on, the community can deal with it, she said. A Villanova University grant supported the project.

“It was shocking for some of them, but I think they also felt empowered because the hands-on experiences helped them see clear, concrete things that could be done to reduce impacts, like raising bridges, putting one-way valves in rainwater sewers or simply using thoughtful town planning,” Poland said. “I think a lot of the anxiety young people, and people in general, have about climate change is due to the feeling that it is some ominous dark cloud racing towards us that is too big or too unknowable for us to do anything about. Helping people build a specific, exciting vision for a future with climate change is the best way to turn apathy and anxiety into action, and I know the students got that from their experience with the Landscape of Change project.”

THE STENCILS

A big part of the mission of the Landscape of Change project, which is, according to the Mount Desert Island Historical Society a “collaborative project using history, science, and imagination to document and communicate the scope, speed, and scale of climate change on MDI,” is to get people thinking and talking about the sea levels and changes.

Since 1950, the sea level in Bar Harbor has increased (or risen) 8 inches. It’s expected to rise an addition foot by 2050; it’s predicted to rise three feet by 2100. The impact is obvious when you start to look.

“There,” Bench pointed out on a walk through the Oceanarium’s salt marshes, “you can see the ghost forest, the salt water incursion.”

The higher the sea water rises, the more small animal homes, more spruces, it takes.

“We don’t want people to feel like we’re powerless,” Bench said about the impact to infrastructure or the island.

Cumming agreed. It’s about knowledge and preparation and working together as an island-wide community to deal with the issues, they both said.

It’s also about looking at the past and making history relevant, Bench said, creating a community understanding and community solutions.

“Let’s start really looking at the coastlines and the changing coastlines of MDI,” Bench said.

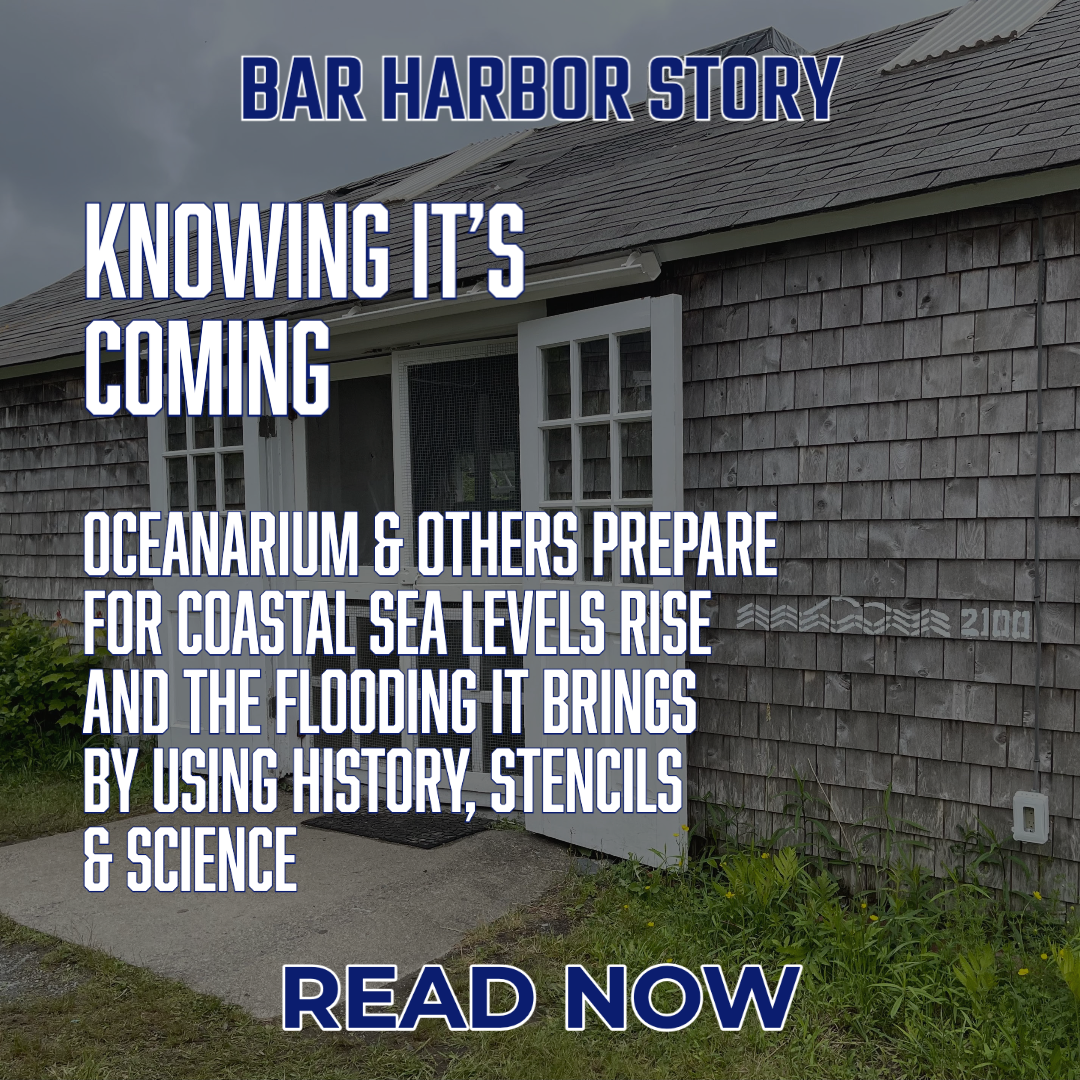

Part of that route to success is to get people thinking and being able to visualize the future. To that end, artist Jennifer Steen Booher and Bench took stencils that Booher created and marked the Oceanarium’s campus to show how deep the water was in the December storm as well as predictions for a similar storm’s impact would be in 2050 and 2100 as well as what the average sea level will be in the area.

The 2100 stencils is three feet above current average high tide. The white 2100 is the level if a storm like the December 2022 came again. As it stands now, the 2100 sea level and stencil is predicted to be 3 feet above current average high tide, which is the same as the storm/king tide levels of December 2022 storm.

The 2050 blue stencil is one foot above current average high tide, which is the currently predicted increase. The 2050 white stencil is the level if a storm like the December 2022 storm came. As it stands now, 2050 is predicted to be one foot higher than our current average high tide.

The 2022 stencils represent the December storm.

Out in Somesville, local fisherman Rusty Taylor marked the Somesville Dam and Fishway with the height those December floodwaters reached.

Those stencils are available for people to use. Bench has kits (including stencils) and information so that people can visualize for themselves where that sea level will be and future storm levels and king tides.

“But use chalk, not paint!” she cautioned.

On August 3, 2023, there will be another king tide and Bench hopes that people will document and send it to the society so that it can share that information now and for the future.

The stencils are part of the Landscape of Change project, the historical society’s initiative with Acadia National Park, Schoodic Institute, the Mount Desert Island Biological Laboratory, College of the Atlantic, and A Climate to Thrive. The Landscape of Change project won the American Association for State and Local History’s Award of Excellence in 2022.

For more information on this and many more of these projects, or to borrow some stencils, visit www.mdihistory.org/wechangewiththem, email info@mdihistory.org or call (207) 276-9323.

LINKS TO LEARN MORE

https://tidesandcurrents.noaa.gov/sltrends/sltrends_station.shtml?id=8413320

Schoodic Institute's Imaging the Future Shore with MDI High School

Cool story maps about the area

NYT article about rising sea levels

The NOAA map to visualize sea level rise.