The Chemicals That Don't Go Away

High School and neighbors trying to find answers about PFAS contamination

BAR HARBOR—Before the public forum about forever chemicals and wastewater began at MDI High School Monday night, people murmured as they sat down in the chairs in the high school’s music room. They murmured about sharing information, about whether the high school or state would consider paying the costs to residents to check their wells for forever chemicals, and whether or not anyone had any answers about why the chemicals were there in the first place. And some murmured about how their kids, high school students, won’t drink the water out of the fountain still, even though it’s treated, because they think it smells bad.

And at least one couple in the audience, waiting for the meeting to start, already knew that their well has been contaminated. At a March meeting of the Mount Desert Island High School Board of Trustees, David MacDonald and his wife Caroline Pryor had already told the trustees that they are concerned.

Their family lives downstream from the high school. Their well? It tested positive for PFAS. Pryor said it would cost $4,000-$5,000 for a filter for the well. The filters remove the PFAS.

MacDonald said at that March meeting and reiterated May 15 that they want the school to be proactive. They want the school to communicate with their neighbors. They want the school to think of their neighbors, too.

And he said that Maine’s been a leader in PFAS; the school can be a leader, too.

“I can’t tell you how much this has impacted our enjoyment of our property,” he said.

He encouraged other people to test their wells and for the high school to determine the source of the contamination. Now, he and Pryor worry about their gardens, their chickens, and obviously their drinking water. A filter can be placed on impacted wells, but the cost is high. Just testing can cost $400 to $500.

Superintendent Mike Zboray, Principal Matt Haney, and John Pond from Harley-Ward Engineering and Environmental Consulting sat at a table lined with plastic water bottles, facing the crowd of over thirty people and explained what had happened and what they knew about the PFAS, the remediation, and also the wastewater systems, which are linked since the water that is now filtered by the school had high levels of PFAS, which is then filtered out into the wastewater system. The sanitized water is then sprayed onto a back field.

In July, the school’s drinking water was tested for PFAS, which are per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, often called “forever chemicals.” Maine tests for PFOA, PFOS, PFNA, PFHxS, PFHpA, and PFDA.

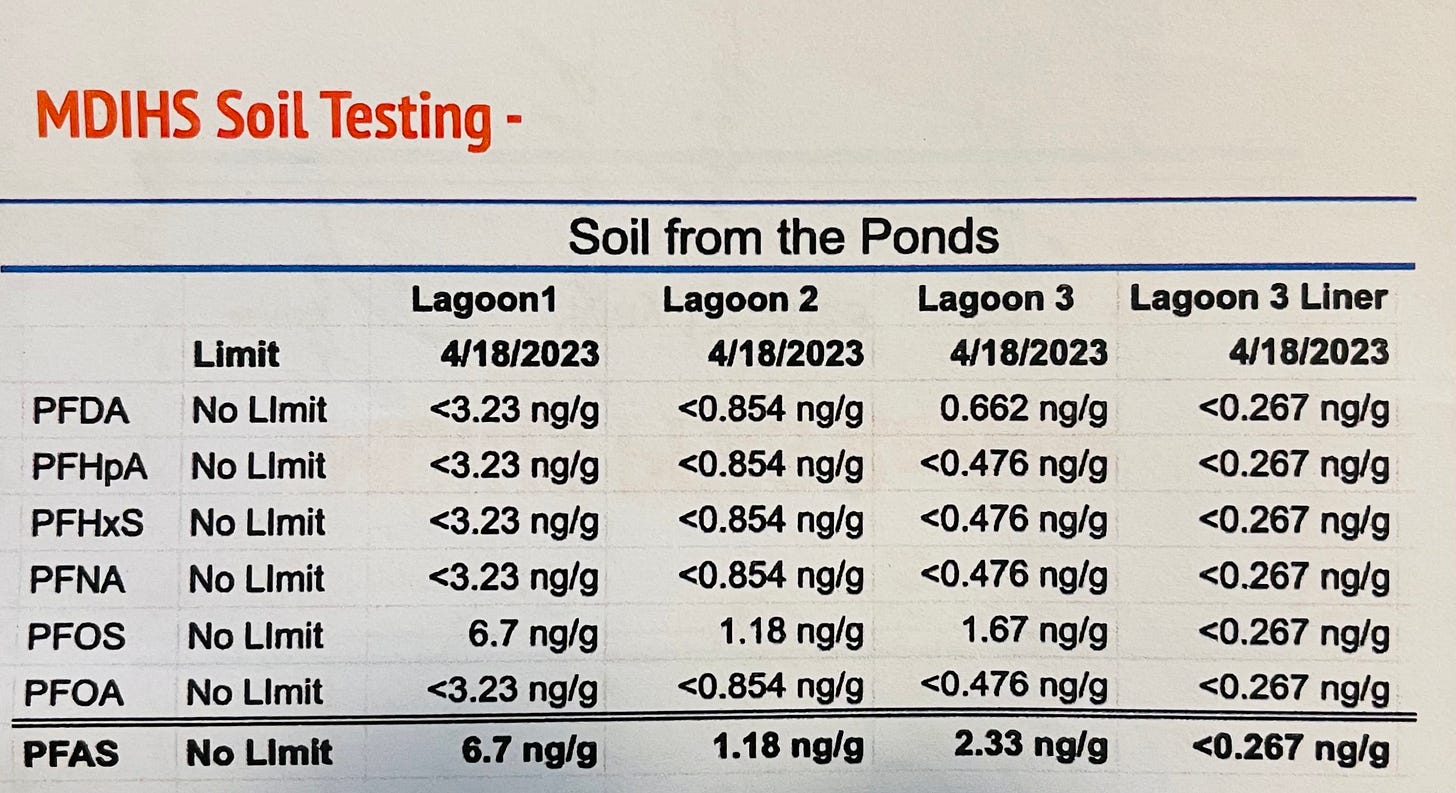

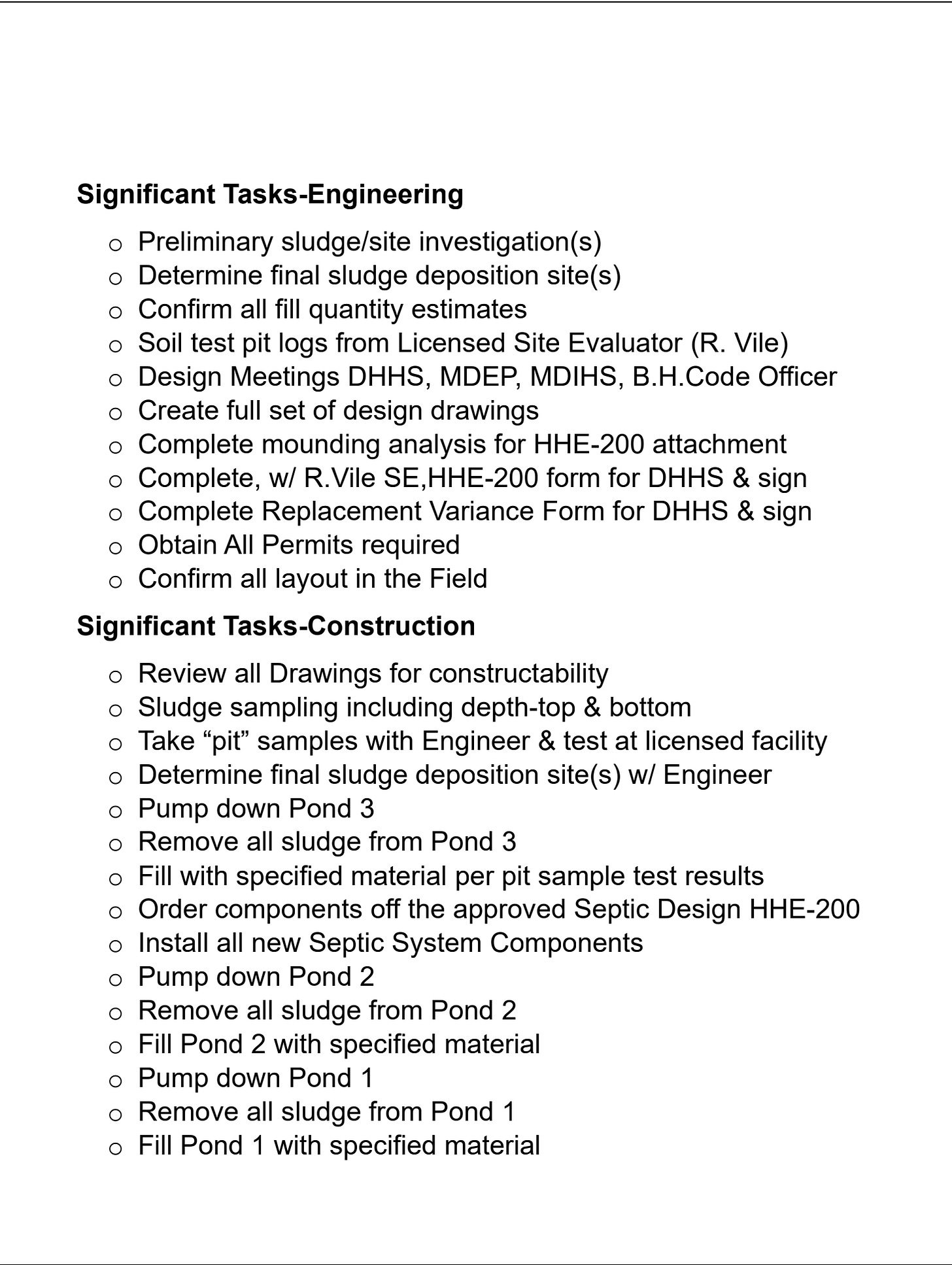

According to Haney, in Spring 2022, Scott Watson, director of maintenance, started asking questions about the wastewater system. It was his first year on staff. Butch Bracy has maintained his license to run the school’s wastewater system. The wastewater is treated using a 37,000 gallon septic tank, followed by three facultative lagoons, which filter the wastewater prior to its return to the environment. This system was designed in the 1960s when the school was built. The sanitized water is then sprayed off seasonally on approximately 3.8 acres of the school property, which is considered a licensed spray irrigation site.

Pond said that the water sprayed is sanitized and dispersed only on the school’s land. This prompted a man in the back row to ask about some students who allegedly were sprayed with water this week and if they were safe.

Pond said, “I wouldn’t recommend walking through an active spray site,” and said that they should be fine.

The man also spoke of how when he used to walk his dog back near the spraying area, he would see a ‘Do Not Enter, Live Parasites’ sign. “I turned around,” he said about what happened when he saw the sign. “The dog didn’t want to, but I did.”

Pond said that it’s a seasonal spray system where the sanitized water is sprayed off between April 15 and November 15 or December 1. The affluent that goes into the field is tested periodically, he said. And throughout the year some of the three lagoons that hold the water are meant to treat that water and some are meant to simply store it. The license for the system is renewed every five years. The last renewal was 2020. The DEP has not requested that it be shut down, but it needs some work, Pond said, because it is leaking.

Kaye Graves owns abutting property to that field. About 25 years ago when the system was put in she said, “I was told this was the purest of water coming out of the pond.” She added, “There isn’t much wildlife up there. It really is nasty looking when you walk.” She recently walked near the property line, she said, and her clothes were sprayed. She said the trees up there look as if they’ve been sprayed with oil.

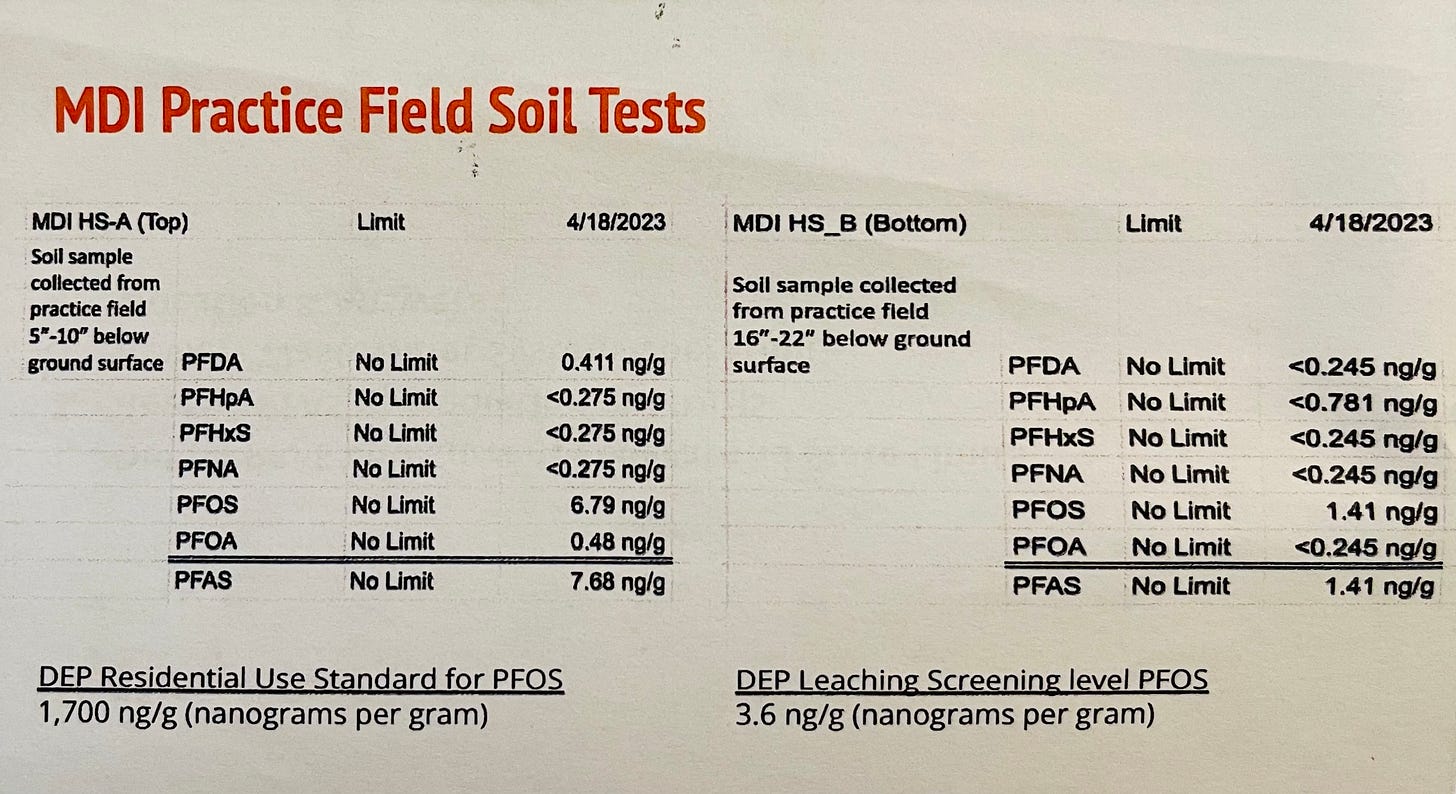

The school had outside agencies test the lagoons and practice fields for PFAS. The field is considered very low for remediation needs, Zboray said.

THE EMERGENCY THAT WASN’T

This spring, Haney told those gathered, the middle lagoon was believed to be leaking significantly, about 100,000 gallons in a couple of days. “It was an all-hands-on-deck emergency,” he said. There are ten million gallons of wastewater in the middle lagoon or pond.

There was construction going on at the third lagoon when the second began to leak, which compacted the problem. The school began the expensive process of trucking the water to Ellsworth. The PFAS in the water, he said, was at a level that allowed Ellsworth to take it.

However, during an early May meeting, it was determined that it was “highly unlikely” that the lagoon was leaking at that rate. This was good news because, according to Pond, it wasn’t sustainable to continue to haul the water offsite because of the cost and the sludge in the lagoon. Landfills are already currently overwhelmed with sludge from wastewater facilities, he said.

HOW FAR DO PFAS TRAVEL? THE EMERGENCY THAT COULD BE

For the neighbors who found PFAS in their well and who worry that it’s contaminated their garden and chickens and for other nearby neighbors who also have wells on their property, there was concern voiced about how far the forever chemicals travel.

Zboray said that to understand that, you have to understand the topography of the land and how the surface water and ground water move. He said that they haven’t seen a significant spread historically of water leaving one site (like the high school) and impacting others. The high school has several streams that lead off it, including one toward Somes Sound.

A February 2023 article in The Guardian writes,

“The substances’ grease and water repellent properties enable them to be very mobile, which means that once the chemicals have departed their original products they can slide their way out of old landfills for example, and migrate into the environment.“That’s bad news because many PFAS also tend to bioaccumulate, which means they are absorbed by organisms faster than they can be excreted and will build up over time. PFAS biomagnify up food chains too, supplying apex predators such as orcas with hefty doses at mealtimes.”

FUTURE OF THE WILDLIFE

Rich MacDonald worried about what would happen to the wildlife that makes the lagoon and pond system its home if the high school switched to another kind of wastewater treatment system and got rid of the lagoons.

He said that there were at least 100 painted turtles, birds, and wild grass making the area their home. Another audience member said that she’s seen a snapping turtle. People also asked if it was safe to remove the creatures located in the habitat if they’ve potentially been exposed to forever chemicals.

Zboray said currently the only limits on the PFAS contamination are about drinking water.

Pond agreed saying, “It’s a wildlife haven back there.”

There’s also an associated cost with getting rid of all the water in the ponds, the soil, and the clay linings. There’s a balance between taking care of the environment and not economically straining the community, Zboray said, and they still don’t know the amount of PFAS that is leaving the school and going into that wastewater system.

The men agreed that there were a lot of questions about the future of the wildlife and that this was an important question.

While PFAS can be filtered out of water to approved levels, there’s currently not a way to remove the chemicals from soil other than the removal of the actual soil completely.

WHERE IS IT COMING FROM?

One of the biggest mysteries is where all the PFAS that’s ended up in the school’s water and wastewater systems is coming from.

Zoboray referenced forever chemicals in polyester clothing, fire resistant clothing, wax for skis, the fiber in carpets. “They are everywhere.”

A woman in the audience also referenced Teflon pans as contaminants. It’s true. PFAS is not just from floor wax and carpets. It’s also in tons of sanitary products and paper products and it is especially in our toilet paper. Jeffrey Kluger cited a study by University of Florida’s Timothy Townsend wrote in a March 2023 article for Time,

“Overwhelmingly, the PFAS that was most present in both toilet paper and in sewage was a species known as 6:2 diPAP, which, as one 2022 study showed, has been linked to impaired testicular function in men. This one chemical represented 91% of all of the PFAS detected in the toilet paper samples and 54% detected in the sewage sludge. Toilet paper usage overall was estimated to contribute up to 80 parts of 6:2 diPAP per billion per person every year to wastewater. That is an alarming figure given that the EPA generally measures dangerous levels of PFAS in water supplies in the parts per trillion, not billion.

“’Our results suggest that toilet paper should be considered as a potentially major source of PFAS entering wastewater systems,’ the researchers wrote.”

And then there is sludge. Sludge is residue from wastewater treatment plants. It’s a semi-solid byproduct that occurs when wastewater is treated.

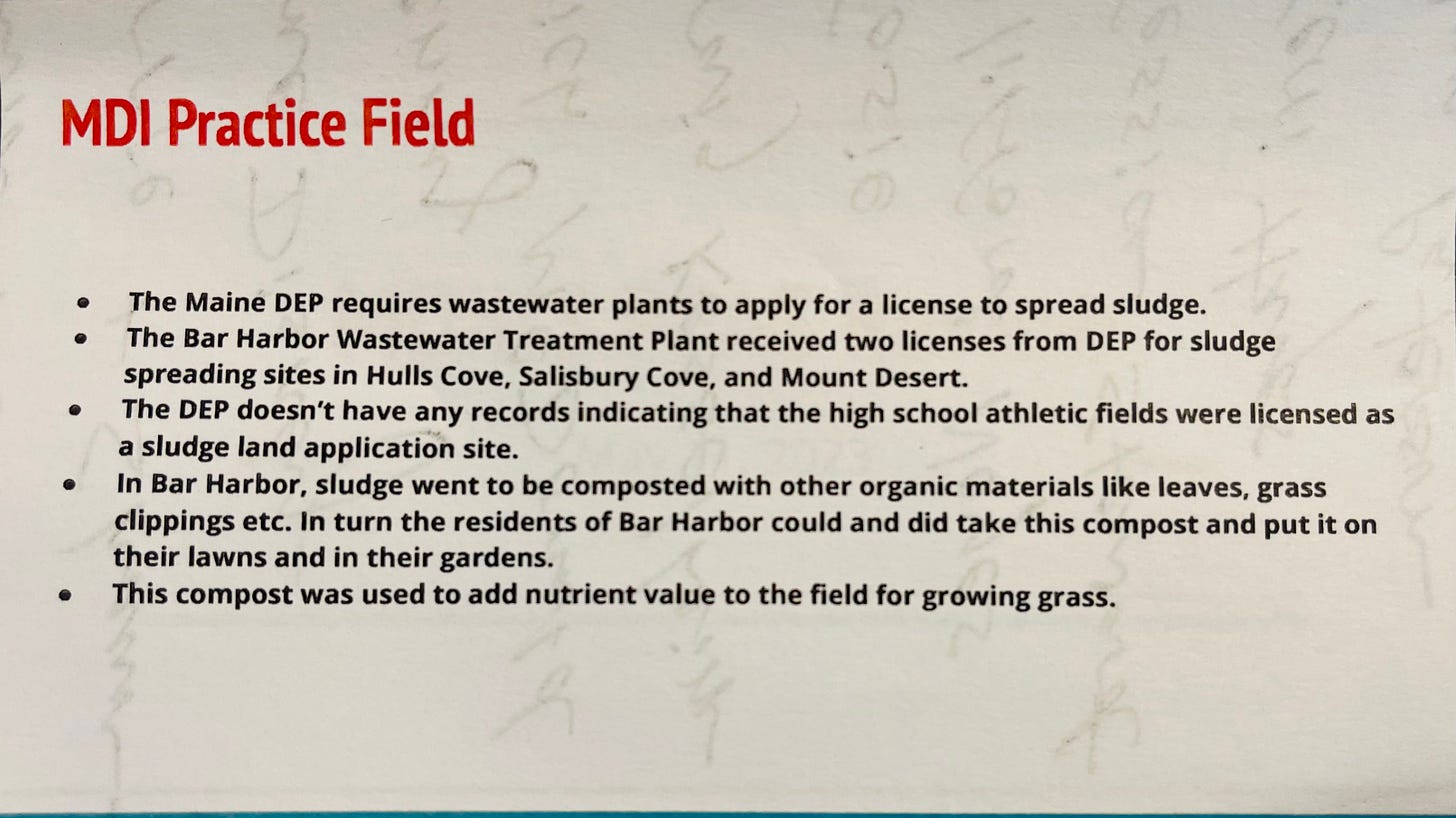

Since the 1970s, the Department of Environmental Protection has been requiring wastewater plants to acquire licenses to spread sludge. The Bar Harbor wastewater plant received licenses to do so in Hulls Cover and Salisbury Cove. However, Zboray said that in the past, sludge was also mixed with leaves and grass. Residents could use that compost to spread it to grow grass and gardens.

“This is probably what happened out on that field as far as we can tell,” Zboray said.

Kruger wrote,

“PFAS are found pretty much everywhere: in soaps, shampoos, cleaning products, clothing, food packaging, plastics, firefighting foam, carpeting and, as recent studies have revealed, in menstrual products, including tampons, pads, and period underwear. The chemicals contaminate the soil surrounding manufacturing plants and have been detected in the water supply—at least in communities that bother to look. There is no national mandate that water supplies be screened for PFAS, but the chemical’s presence in toilet paper provides one more route it can take into groundwater, drinking water and, eventually into us. And it’s not as if we or other creatures need another exposure route. PFAS have already been detected in wildlife, human blood, and breastmilk.”

Jessica Stewart, the chair of the Mount Desert Island Regional School System-AOS-91 School Board, said, “We don’t actually know that the PFAS is coming from the school at this point.”

Pond said, “PFAS is everywhere right now, probably in all of us. PFAS, it just doesn’t go away. It doesn’t break down, so it stays in the environment for a very long time.”

When asked if there was a landfill at the school that could possibly be causing the high levels, all the men said no.

At the March meeting, Pryor had asked if the school knew where the PFAS was coming from and if the school itself was generating it. During that same meeting Athletic Director Bunky Dow said that there is municipal sludge on the upper practice field. Soil and grass were also added to that base of sludge, which could be contributing to the PFAS, which are also in the school’s well.

At that same March meeting, Scott Watson said that the school was still trying to figure out what to do to take care of the PFAS situation. Watson approached the Hancock County Commissioners who said they wouldn’t fund it (3-0). He also asked the state, which hasn’t answered.

For David MacDonald, it seemed a no-brainer that the PFAS is coming from the high school site, and he asked what other large operation is located and going on nearby that could be creating so much PFAS. He asked about what paper trail exists that could show what went into the upper field and if and how much sludge was used there. He encouraged the school to get neighbor’s wells tested. The football field had been sprayed with the affluent from the ponds for years, he said. And it is wetland twenty feet from those ponds to their property. “The high school is poisoning the well in the cycle” of intake and outtake, he said.

“I would like to ask the district to make a commitment as soon as possible to have a multiparty transparent rigorous examination into the source of the contamination,” Pryor said. “This well is so contaminated and we need to know where that is coming from.” She later added, “You’ve got dozens of neighbors and we have to have accountability and transparency. We don’t know where it’s coming from and it’s serious and it is a loop.”

POSSIBLE HELP FOR NEIGHBORS

Biologist Jane Disney from the MDI Biological Laboratories said that she’s been doing a small study across two states looking at arsenic and other chemicals in wells. “A lot of people we’ve been working with have expressed concern about PFAS,” she said. “It’s so expensive to test for PFAS. We have some limited funding and we can work with the immediate watershed.”

They could potentially work with Maine Laboratories in Norridgewok, which is the first laboratory in Maine that’s running PFAS testing. She said that she hadn’t been looking around the island for a site for PFAS contamination because it hadn’t seemed likely.

BACKGROUND ON THE DISCOVERY AND MITIGATION EFFORTS SO FAR

Over the winter, the high school’s board of trustees authorized JW Goodwin to do preliminary work to investigate the state of the pond and a potential solution. The trustees requested that Haley Ward be brought in as project managers increasing their scope beyond the initial environmental testing responsibilities.

An article by Maine Public last summer states,

“‘The installation of a new water filtration system for the Mount Desert Island High School will begin Tuesday and should be finished by the end of the week,’ said Mike Zboray, the regional school system’s superintendent.

“State testing of drinking water at the Mount Desert Island High School showed PFAS levels at 85 parts per trillion. State officials will return to campus to help the school identify where the PFAS are coming from, which could include a well that provides water for the fields, Zborary said.

“‘They’re going to come and take a look at the separate well that does irrigation,’ he said. ‘There is a small marsh area at the front of the property. We thought that water should get tested as well.’”

PFAS is considered “forever chemicals.” The report on all Maine schools is here.

An article by Joe Lawlor for the Portland Press Herald writes,

“PFAS — per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances — are a large, complex group of synthetic chemicals known as "forever chemicals" because they do not break down well and accumulate in the environment.“During industrial production and application of contaminated fertilizer to farm fields, the chemicals can leach into the environment and get into well-drinking water, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“In Maine, wastewater sludge spread on farms for fertilizer over decades caused PFAS chemicals to creep into drinking water supplies, with especially high concentrations in central Maine. Maine now bans the use of sludge as farm fertilizer.”

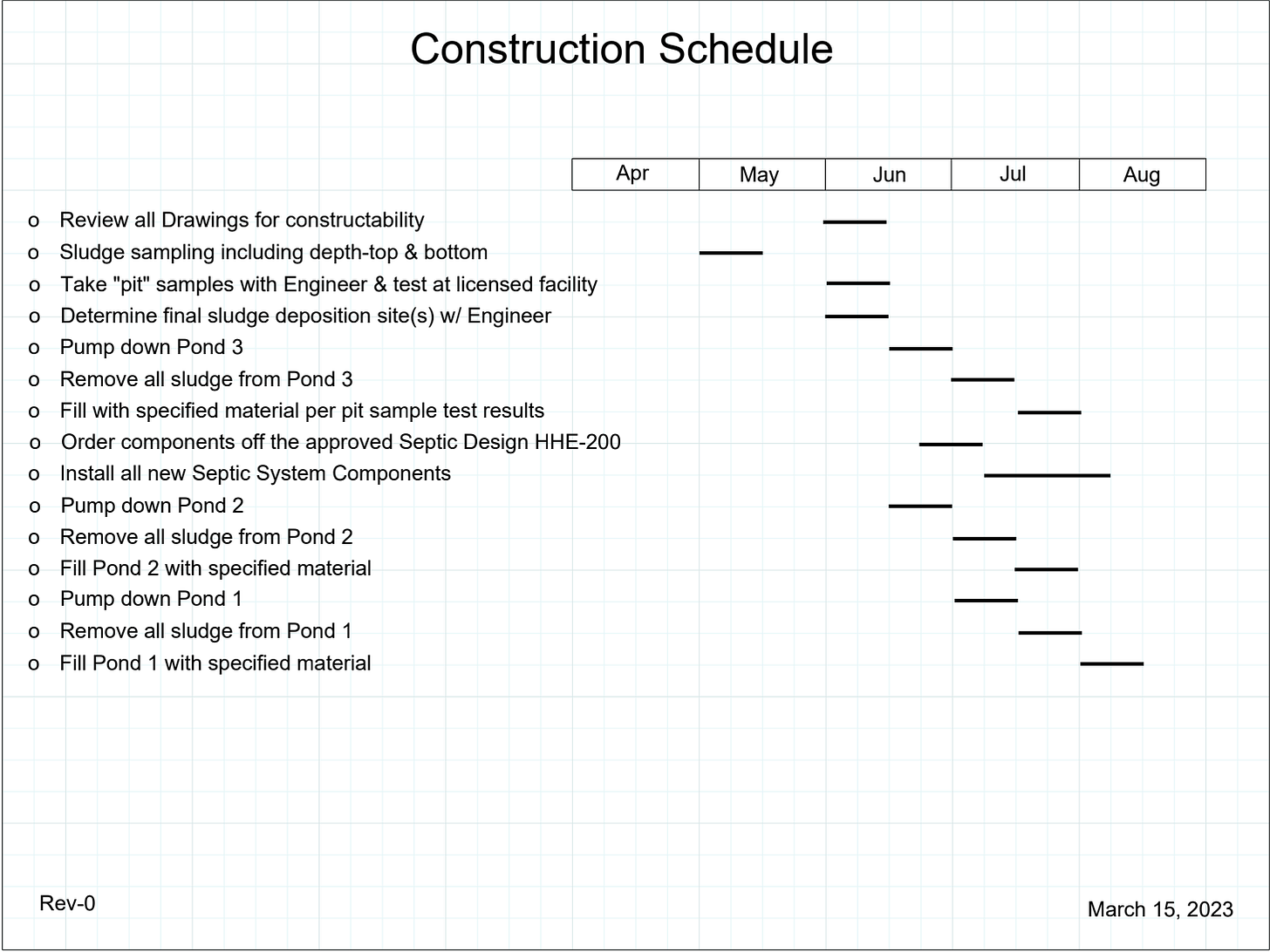

In March, JW Goodwin and Jeff Crafts suggested pumping the third pond on the property into the second so that it can be dredged and then figure out how much fill would be needed on the property to make a septic field. The group moved to proceed to find a company to move the water from the third pond into the second pond to get to the sludge and remove the sludge to do the State-required testing. Mount Desert Island High School Board of Trustees Joseph Cough was the only member opposed, and that opposition was because the motion wasn’t an action item on the published agenda. He believed the public should have been aware that this could have been voted on.

It's unknown how much PFAS in water is safe. The EPA is proposing a federal standard to 4 parts per trillion (for two PFAS chemicals). Maine’s standard is 20 parts for trillion for six PFAS chemicals.

Maine, under its current contamination standards has found high PFAS levels in 25 schools and 502 drinking water sites. Maine has testing programs and remediation programs. There are other bills that could help low-income residents pay for blood tests and require the testing (and disclosure) in real estate transactions and for landlords.

The amount of PFAS in the school’s drinking water in July was 59.8, above the state limit and below the current federal limit. “We immediately began looking into filtration,” Zboray said Monday. “It was installed in August.” They received some grant funding to help pay the $29,000 cost.

LINKS TO LEARN A BIT MORE

https://haleyward.com/leadership-team/

Correction: We added a zero to 37,000 so that it read 37,0000. Many thanks to Ellen Grover for letting us know!