BAR HARBOR—The town’s planning department released the results of two Bar Harbor housing surveys this Wednesday and expects to discuss the material further at the January meeting of the Comprehensive Planning Committee, said Assistant Planner Steve Fuller in an email to the press.

One survey was meant for employers. The other was meant for those who worked in the area. That survey for workers was “essentially three different surveys for area workers, however, based on how they responded to the very first question (which asked where they lived and worked),” Fuller wrote. The worker survey received 751 responses

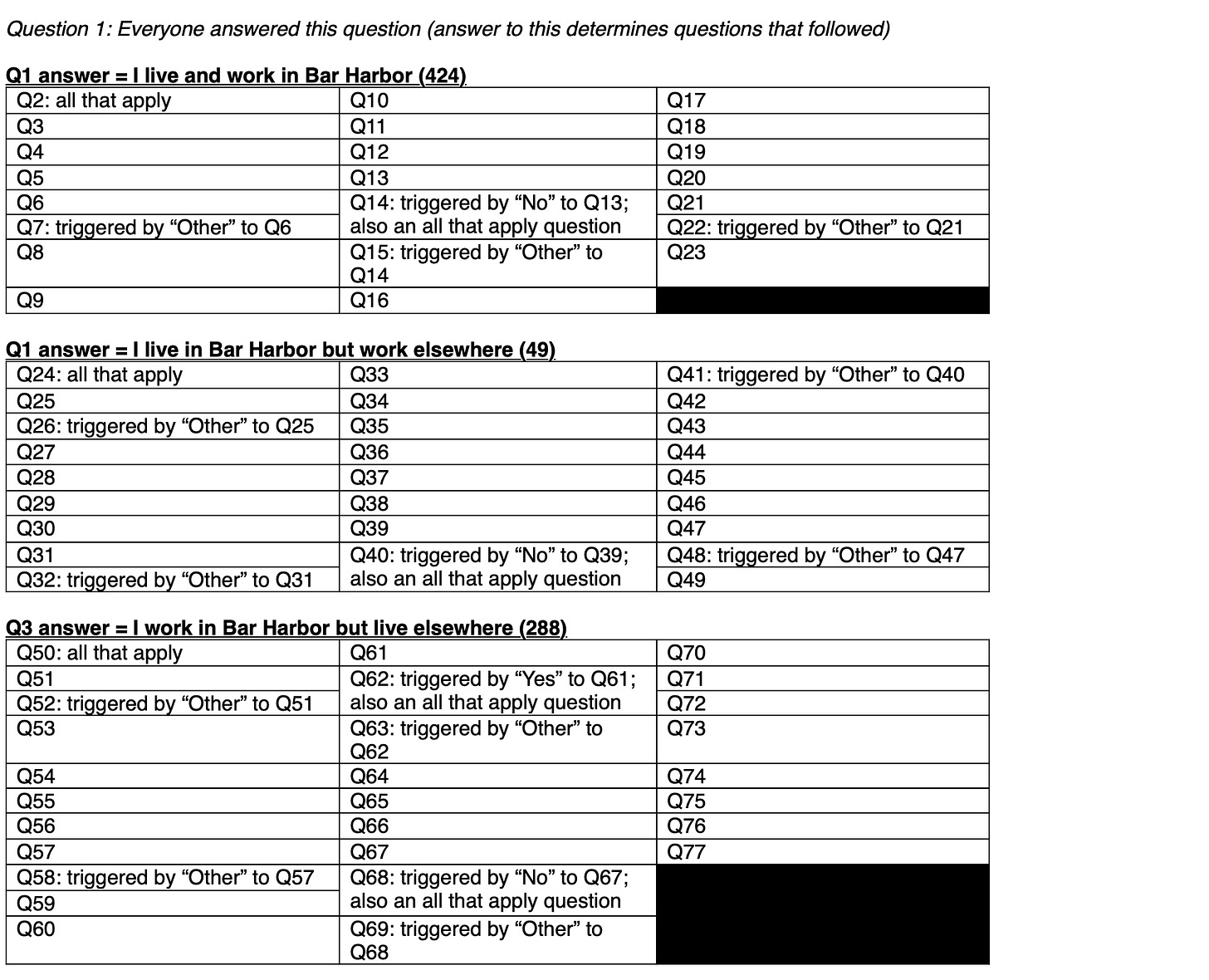

All the POLCO surveys left room for respondents to present thoughts about their own experiences with housing in Bar Harbor. The employer survey asked questions such as the average hourly wage for year-round and seasonal employees

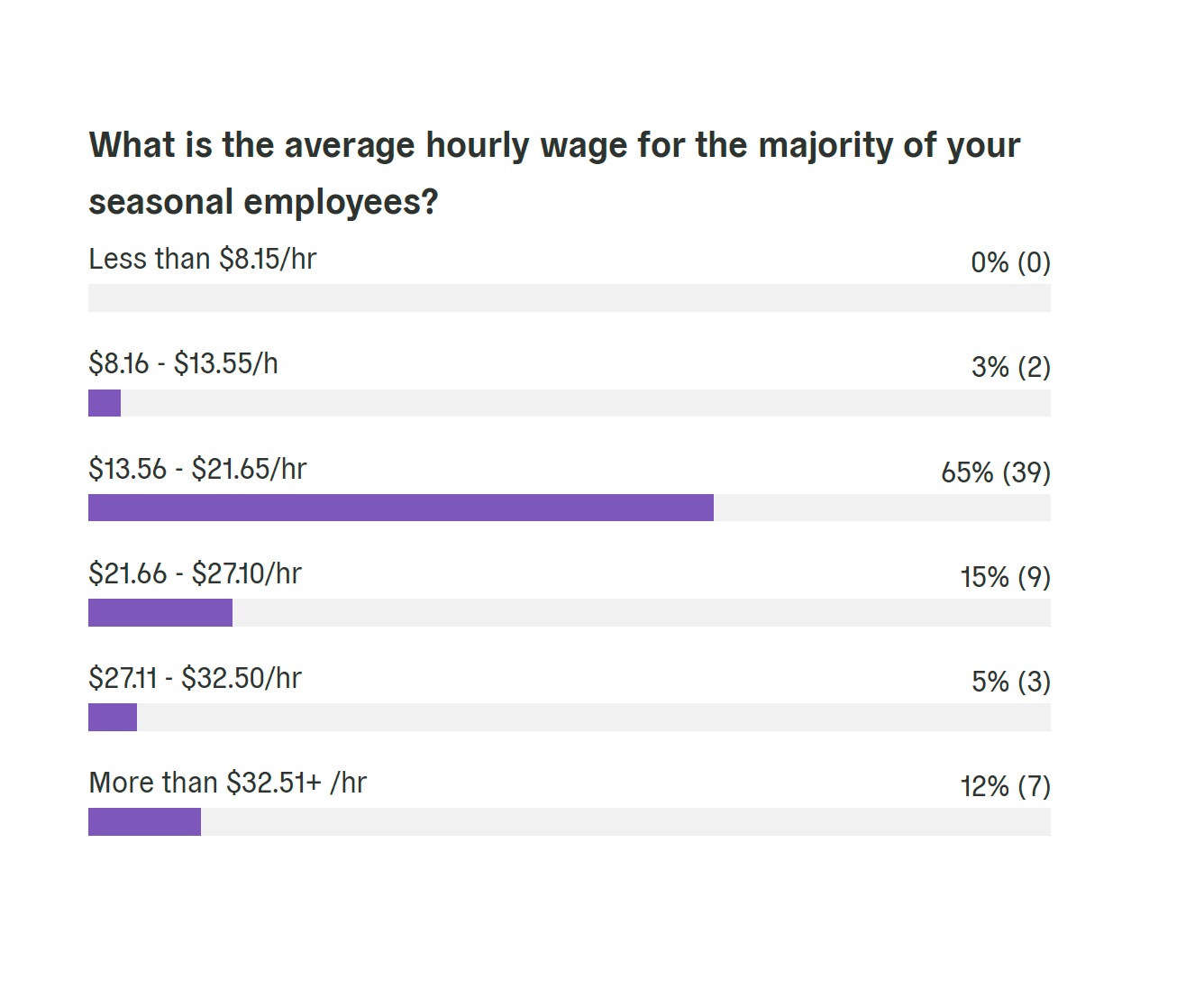

The median household income (in 2021 dollars) for Hancock County, Maine for 2021 was $$60,354 There are approximately 56,192 people in the county.

The U.S. Census Bureau did not have a number of housing units in Bar Harbor listed, but did have an owner-occupied rate and other facts that are included in the charts below. The Bar Harbor mean household income was almost $12,000 more than the rest of Hancock County.

The Bar Harbor survey released Wednesday also asked employers if they had estimates about their employees’ living conditions

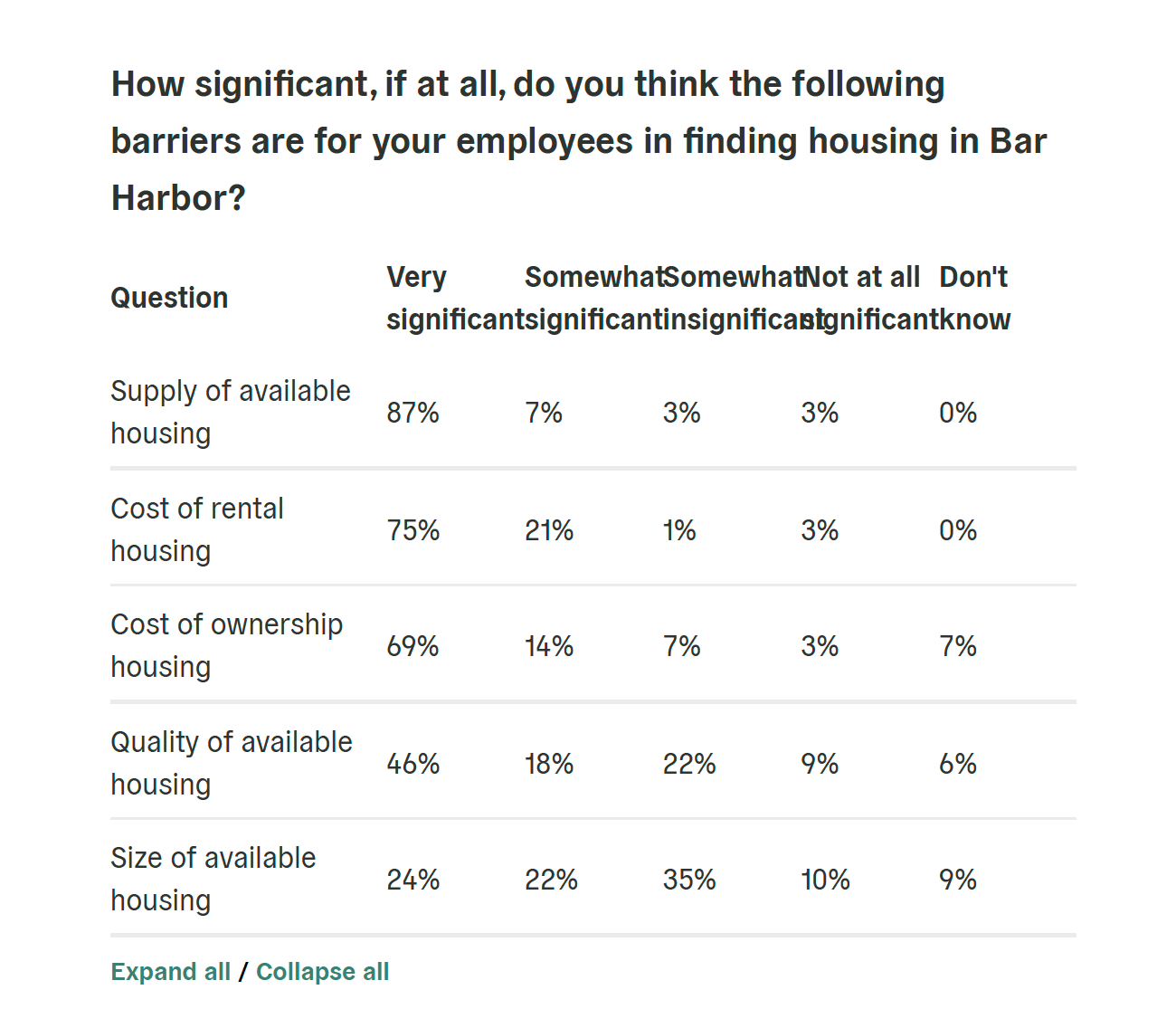

A majority of the employers (84 percent) said that their employees not living in Bar Harbor have difficulty finding housing that meets their needs. Of the employers responding, 76 percent said they lost an employee due to lack of housing or housing affordability in town. It also asked what employers believed were the barriers to housing.

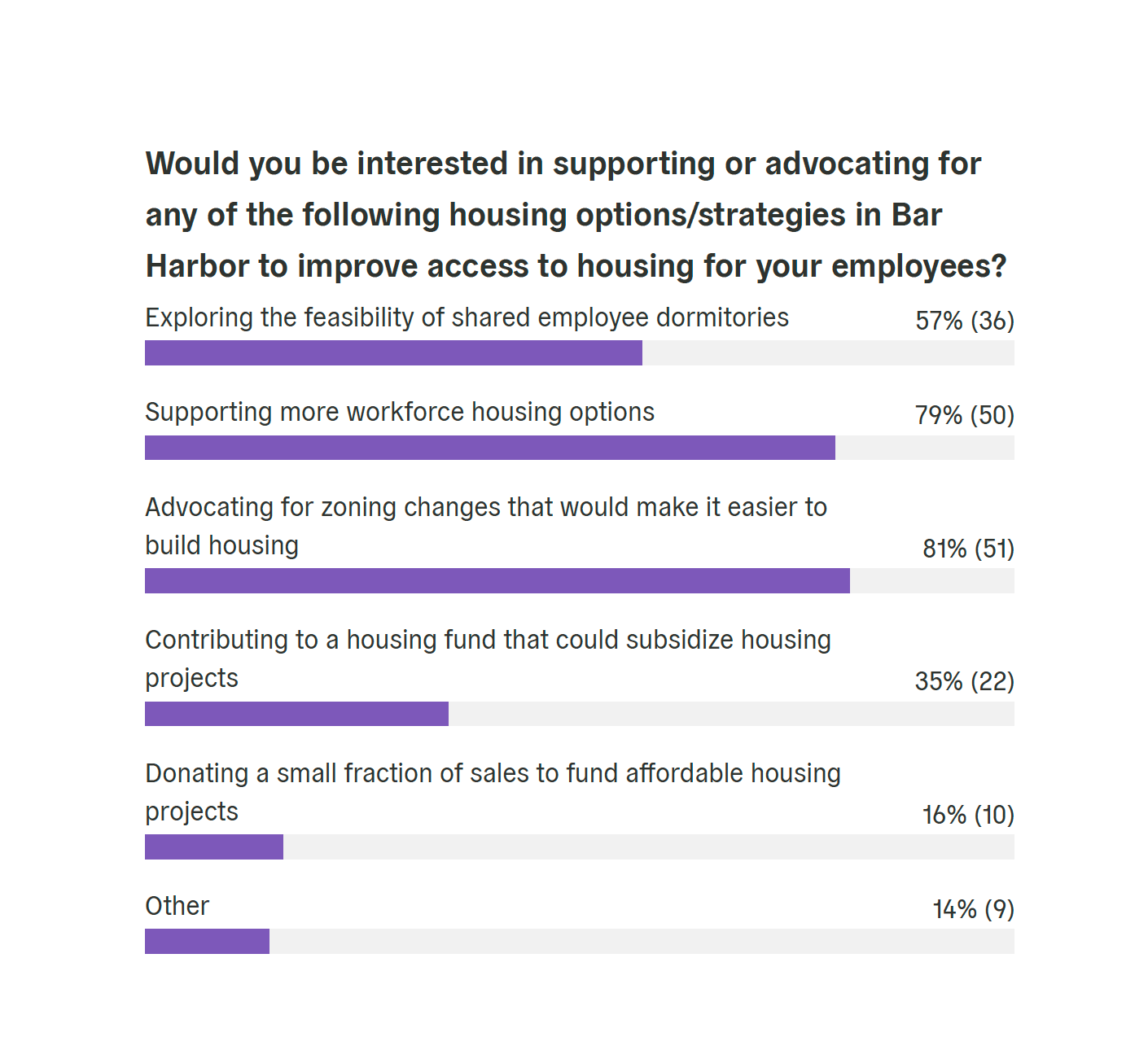

Just over one-third of employers say that they own and provide short-term housing. A similar number says that they help employees find housing. Just over a third do not help employees find housing. About 73 percent of respondents say that they do not restrict the number of months they are open due to a lack of year-round employees. The survey also asked those responding if they would support or advocate for a number of options and strategies about housing.

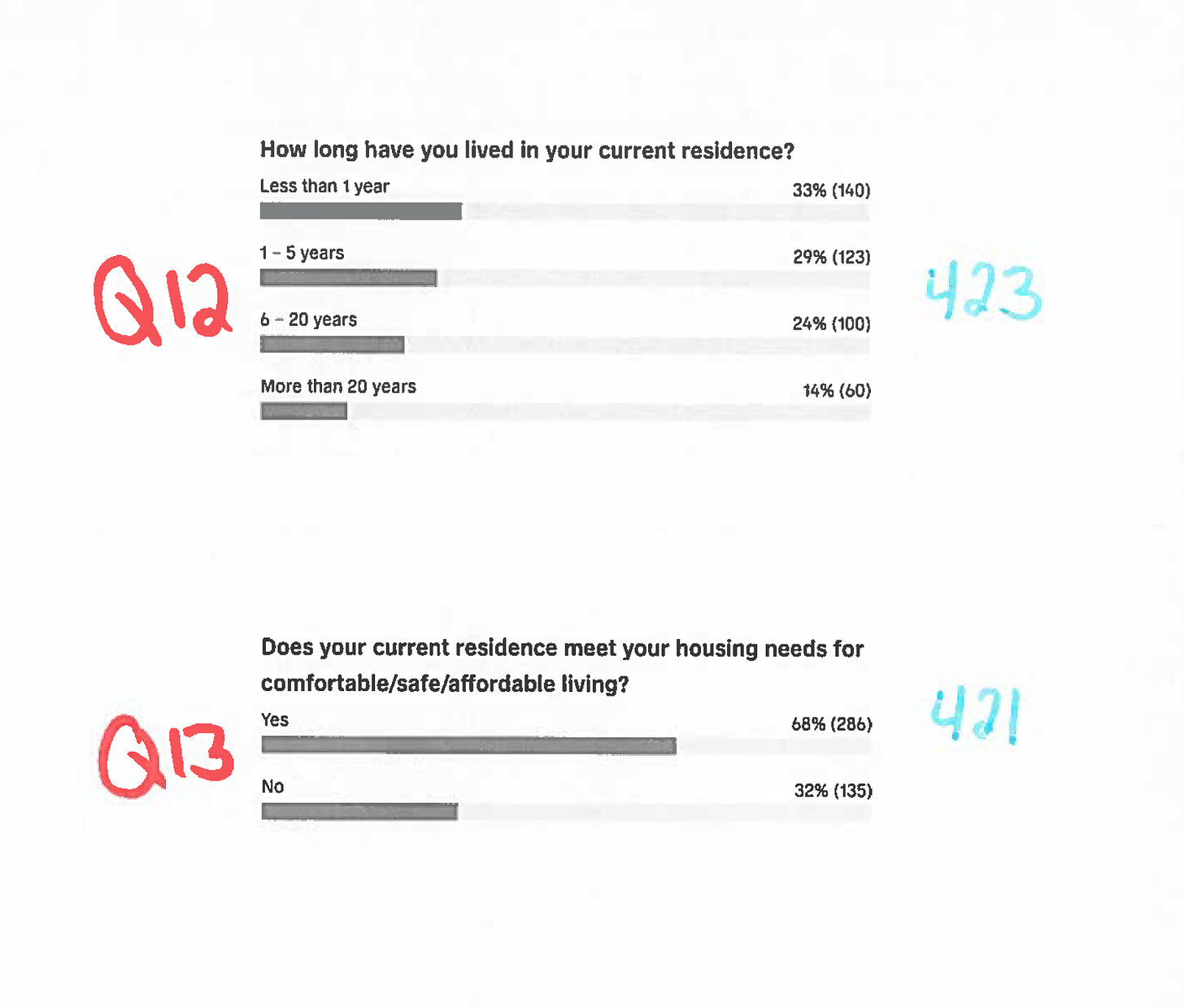

Of the 424 people who responded who live and work in Bar Harbor and responded, only 7 percent didn’t have permanent housing. About one-third lived in their current residence for less than a year

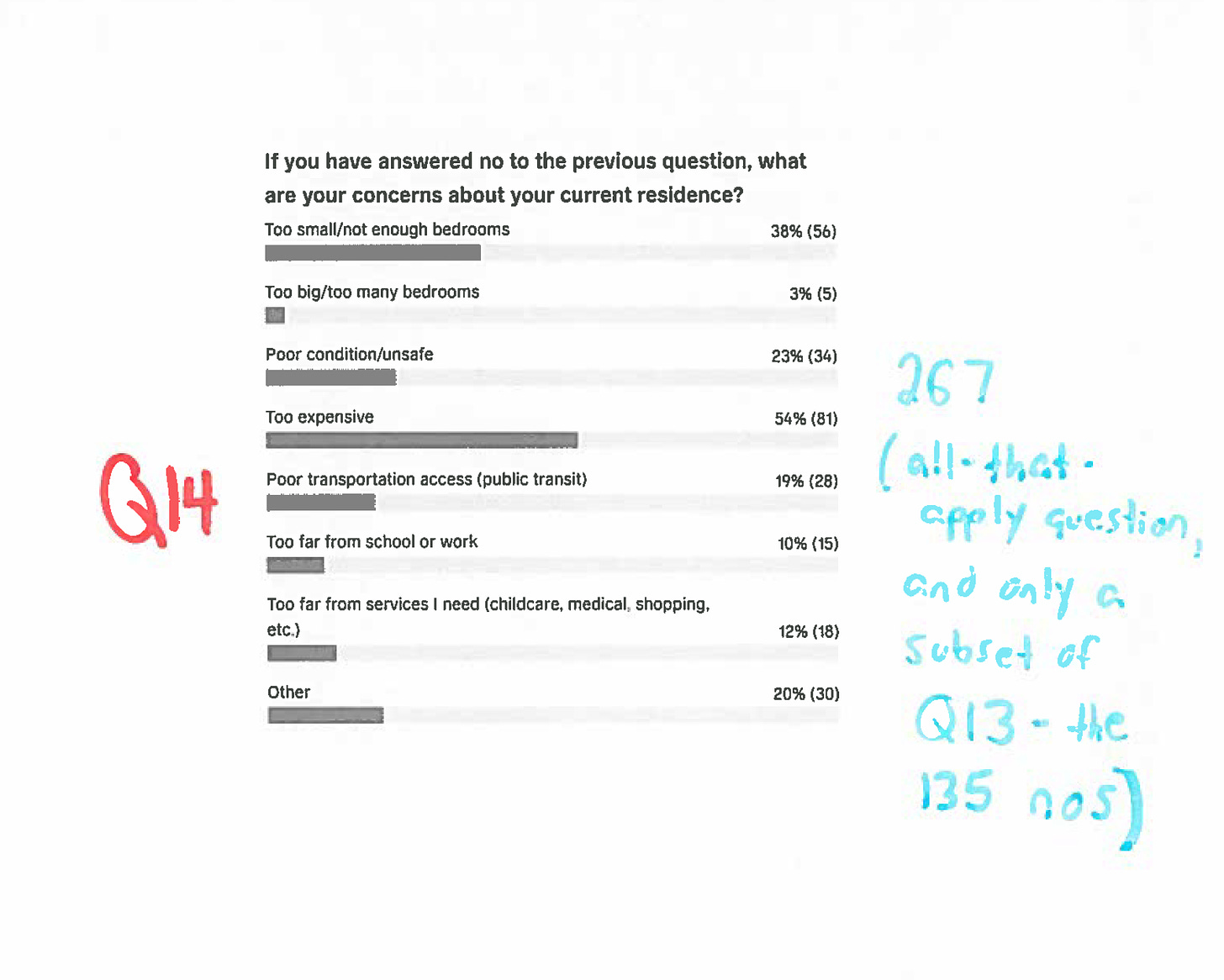

Of those who don’t find their housing meets their needs, more than half said that it was too expensive. Of the respondents to that section of the survey, 39 percent paid less than $1,000 for monthly housing including rent/mortgage, utilities, insurance and taxes. More than 56 percent paid less than $1,500. A quarter of the respondents who live and work in Bar Harbor were under 25. The majority of respondents (in that same demographic for the survey area—68 percent) were between 25 and 64.

Of the 288 respondents who work in Bar Harbor and live elsewhere, 90 percent were full time workers and 48 percent of those earned between $13.56 and $27.10 per hour. An additional 51 percent made over $27.11 an hour. Only two respondents of this demographic (live here, work elsewhere) to the survey made less than $13.56 an hour. Of the respondents, 61 percent would like to live here and 39 percent would not.

Of those who live elsewhere, 59 percent had challenges finding their current home.

According to an article by Freddie Mac,

“The Bureau of the Census reports that in 1980, 40 percent of homes constructed were entry-level homes. In 2019, only 7 percent of homes constructed were entry-level homes.”

The problem with affordable housing is both nationwide and local.

“Affordable houses don’t exist anymore” when it comes to building starter homes said Linda Farnsworth Higgins who has been a realtor and broker at LS Robinson since 1987 told the Bar Harbor Story for an October article on obstructions to starter homes (linked below).

Higgins said one reason is the cost to buy land and then to bring in septic, utilities, and putting in a well. Even a home without upgrades like granite countertops are coming in around $350,000 or $400,000 to build, she said. With currently the increasing interest rates, that’s been putting those homes just out of reach for a lot of buyers.

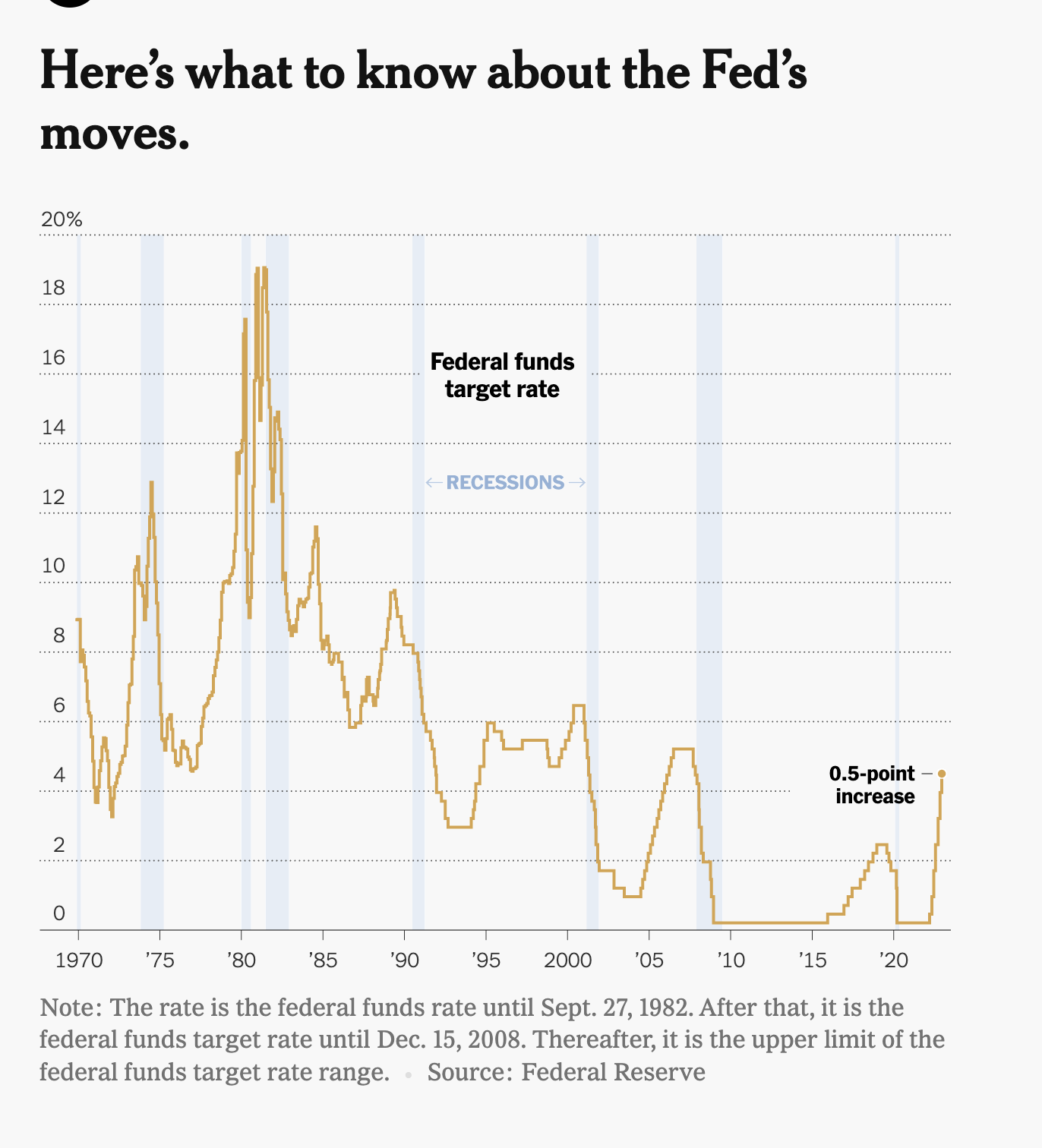

The central bank increased interest rates a half a point December 14, the day of this article, which is a slightly slower pace. It is now at 4.5 percent, a new high. The last time it was 4.5 percent was 2007.

On September 25, the New York Times’ Emily Badger wrote a feature “Whatever Happened to the Starter Home?” where she said,

“The disappearance of such affordable homes is central to the American housing crisis. The nation has a deepening shortage of housing. But, more specifically, there isn’t enough of this housing: small, no-frills homes that would give a family new to the country or a young couple with student debt a foothold to build equity.”

Badger writes that multiple factors have created this housing shortage. Land costs more. Like Higgins said, the cost to build houses is more expensive because of building materials and labor costs. There are a lot more regulations and fees from governments.

As land and lots became more expensive, she writes, instead of decreasing required lot sizes to build on, towns and cities increased the minimum lot size. They also often created stricter rules about setbacks and design. And those changes often stem from towns and cities trying to make their best communities, Badger says.

The development study that town councilors will hear about on Monday is part of the 2019 Housing Policy Framework’s strategy #4, which is meant to “identify if the LUO (land use ordinance) creates barriers to the development of affordable workforce housing.”

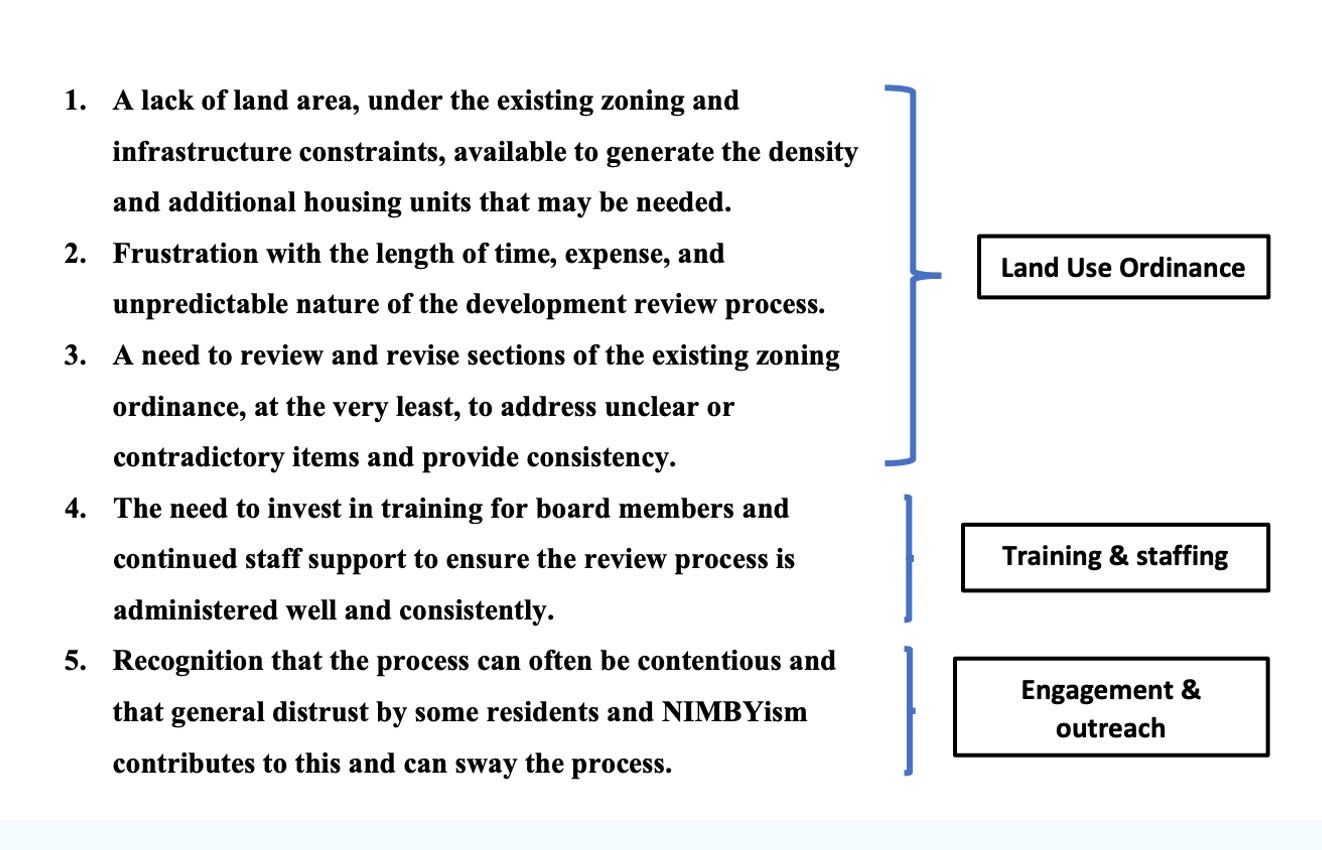

The conversations with twelve local professionals found that:

Among many possible actions to “remove barriers to development” the report recommends “revising the foundation” of the town’s “land use ordinance to simplify the administrative framework and procedures such as conflicting language” and also to “explore: a) decreasing the number of and/or combining zoning districts; b) revising dimensional requirements including setbacks, height, lot coverage and housing density; and c) revising parking setbacks from roads.” It also mentions potentially expanding where employee housing can be situated within the town as well as “look at other options such as employee campsites.”

Realtors who wished to remain anonymous for the article said that despite Bar Harbor’s short-term rental ordinances which caps certain types of vacation rentals, there is no increase in affordable housing supply. Higgins said that other communities have seen an increase in property buyers purchasing homes to host vacation rentals. One realtor said there may be a few more long-term rentals on the market since that change, however, most of those are offered for over $2,000 a month.

An August 11, 2022 Portland Press Herald piece states,

“The enforcement of a cap on non-owner-occupied rentals in Bar Harbor, for example, has led to spillover into neighboring towns, according to recent reporting, spurring these communities to consider caps of their own.”

Many in the survey expressed displeasure over the existence of short-term vacation rentals, which Bar Harbor has capped the amount of. Others said that they arrived 19-25 years ago and had difficulty finding housing then. There are many responses that detail people’s own situations and worries and some that suggest ways to deal with housing issues. Many of those same ideas are in the housing policy framework created by the town.

Of the transitioning of dwellings and apartments into Airbnbs, AirDna writes,

“Supply growth has since calmed in the face of falling revenue premiums (and after expanding in the first half of the year). We expect the number of active listings to increase by 21% in 2022, in line with our previous forecast. Additionally, the number of nights supplied will increase even more, to 25.3%, as existing and new listings broaden their availability. In 2023, growth for nights listed will be 9%, less than in 2022, as the pinch from lower profit potential is felt.”

The organization also predicts demand for short-term rentals will be steady but “slowed due to economic realities.”

All of those questions about development, zoning rules, property setbacks, property uses, rental properties, seasonal worker housing, and more are a sliver of the Comprehensive Planning Committee’s duty when trying to create a document that’s driven by data rather than anecdote as it the guides Bar Harbor’s officials and staff for the future. The housing surveys are now a part of that data and documentation.

“This information will be discussed in more detail at the January meeting of the Comprehensive Planning Committee, set for Wednesday, January 11, 2023 at 6:00 P.M.,” Fuller wrote.

The public can attend the meeting, which will be held in the Bar Harbor Municipal Building on Cottage Street. Usually those meetings are held in Council Chambers and also streamed.

LINKS TO LEARN MORE

https://www.nytimes.com/live/2022/12/14/business/fed-interest-rates-inflation

Bar Harbor Comprehensive Plan links.