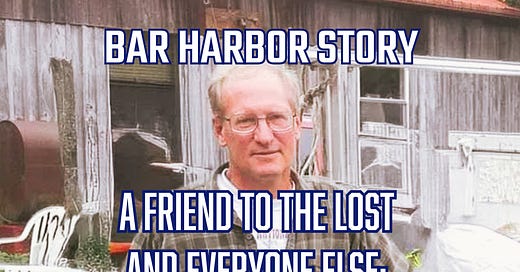

BAR HARBOR—There was a man on Mount Desert Island who sometimes had a large black bird on his head.

There was a man on Mount Desert Island who would share his love of nature with everyone he met.

There was a man on Mount Desert Island who would lean toward adventure with friends whenever that was a choice.

Magnificent, people called him.

Extraordinary, they said.

Smart. Sweet. Talented. Beloved, they said.

And they were all right.

On April 16, that man died from post surgery complications, which means that Mount Desert Island lost Scott Swann.

“The COA community mourns the loss of professor Scott Swann ‘85 MPhil ‘94. Scott’s ecology courses introduced hundreds of students to the wonders of the natural world for many years, and his infinite curiosity, sense of humor, and expansive heart left a deep impression on all those who learned from and worked with him,” the College of the Atlantic said on social media.

Scott’s life was full of adventure. It’s not everyone who moves a pilot whale carcass in a UHaul. It’s not everyone who homesteads. It’s not everyone who could repair a car, dive for scallops, wax poetic on all things moss.

But even those adventures and skills don’t truly explain who Scott was.

Scott Swann was a friend to the lost, Matt Gerald has said.

A friend to the lost.

According to Anne Swann, Scott and many of those friends he had, built a lifetime of adventures and misadventures.

“A Mount Desert Island resident since 1981, there was not a town or a profession that Scott did not have an impact in. As a student at College of the Atlantic, he supported himself doing just about anything … restaurant work, carpentry, scallop and research diving, occasionally a sternman, land surveys, car repair, museum tech, biologist for hire … eventually landing on a career of teaching and carpentry … usually at the same time,” Anne wrote.

Biology, natural history, and people: all those things intrigued Scott.

“He had the great experience of growing up in the same house in Westwood, Massachusetts and being given freedom to wander the woods around his home and do the crazy stuff that inventive kids regularly do. Scott was the fourth child of two teachers and his father often tried out biology classes with his children before he taught them. This kind of gave Scott a jumpstart on a career,” Anne said.

Once, Scott built a huge observational honeybee hive. It was the largest hive on the east coast.

The thing is that Scott didn’t just build that hive anywhere. He built that hive in his bedroom.

Anne said he’d reminisce about falling to sleep to the sound of the bees.

“He was an Eagle Scout and loved hiking, camping, and canoeing. He volunteered at the Hale Reservation in Westwood, often working with disadvantage kids. Working on his beloved VW Bug with his father gave him a terrific understanding of engines and machines, which would influence him for his whole life. He loved his childhood and his close-knit neighborhood. Walking around the woods of New England with Scott was a really cool experience.… He could find ancient stone walls and house foundations as though he always knew they were there. He could read the landscape with an uncanny ability,” Anne said.

He could read people. too.

The seaweed pressings some students made in his classes still adorn some of their walls. He was formative, they said. He exemplified COA, they said. He was a professor and a friend, they said.

“Scott was truly a remarkable individual, full of life and joy, and his presence will be deeply missed. I am heartbroken to hear this news, but his legacy lives on in the lives he touched and the talents he cultivated,” Morgana Kaelin wrote on Facebook.

Anne said Scott found his calling when he moved to Maine and then attended COA.

“Being mentored by Bill Drury, Steve Katona, Craig Greene, and Butch Rommel set the wandering course of his life,” she said. “At COA the observations from his childhood really came together. He was an active member of Allied Whale and the whale stranding team. Which sometimes meant stopping at his mother’s house on the way back to Maine with a whale carcass in a U-Haul truck. This was not a welcome sight or smell for his neighbors. Or the U-Haul company.”

“Scotty had a great sense of justice, which often got him in trouble…. Once he stole his beloved VW Bug out of the Bucksport impound lot because he knew the arrest (for a tail light that was out) was wrong and—he had a spare key. Another arrest followed and an admonishment to not drive in Maine for seven years followed. Yet somehow, he just went and got a new license. He was charmed that way. It also helped that Steve Katona bailed him out several times,” Anne said.

Katona is the former president of COA.

Scott made things better. He cleaned up roadsides, shared jokes, and was integral to the birth of Bar Harbor’s Oceanarium and Education Center.

“One of the first to put his shoulder to the wheel, he came with a naturalist’s knowledge and a lifelong educator’s willingness to share. When paired with the carpentry knowledge and skill he brought to our needy buildings, our budding effort suddenly looked like it would succeed,” the center wrote.

Scott didn’t teach and share and befriend only in Bar Harbor.

“His love of field research took him all over the world. From the bottom of the sea floor,—censusing of Frenchman’s bay for the Smithsonian, to a farm in Kenya where he spent a year trying to outwit the local crows (the crows won). He climbed Kilimanjaro, and then spent some months wandering with a nomadic Masai tribe. When he returned from Kenya, he widened his skills,” Anne said. “Scott adored the idea of a Natural History museum at COA and loved to prep study skins and marvel at the artistry of making something from nothing. He built a wet-lab at COA and had hundreds of sea anemones he was studying, eventually discovering that a common local species was really two. He worked off and on at Mt. Desert Rock for years and Petit Manan Island, where he began to become interested in colonial nesting seabirds.”

He was a man who called adventure to him.

“At one point, perhaps intrigued by stories from Bill Drury, Scott had an idea to drive a VW Van from Bar Harbor to Tierra del Fuego, Argentina. So, in 1986, with that Scotty Swann confidence, and an old National Geographic map of Central America, he (we) took off. There was no reason this trip should have been successful.… Lack of language skills, political knowledge, and money were a constant problem as that van wound its way through washed out roads and wars in Central America, to gem smuggling towns in Ecuador and the heat of the Atacama Desert in Chile—eventually landing for a three year stint working for Wildlife Conservation Society at Punta Tombo, Argentina studying penguins,” Anne said.

Specifically, Scott became intrigued with how observers affected their study subjects.

“The van and a motley crew did make its way to Tierra del Fuego and the end of the road there, eventually being parked in Santiago Chile, causing a small international incident. Scott went on to climb Aconcagua with COA alum Arthur Kettle … another venture of over confidence and under preparedness. But they made it,” Anne said.

Returning from Argentina, Scott bought an old property on Gotts Island. He started to build a home. He worked out how to hand dig a well. He transported materials. For the first couple years, Anne said, he’d row back and forth to Bass Harbor for supplies.

Stubborn? Maybe. But stubborn is just another word for persistent.

Inventive? Absolutely.

“It was at this time that Scott was asked to teach a continuation of Bill Drury’s class ‘Ecology-Natural History’ at COA that Scott really found his calling. He loved teaching and adored his students,” Anne said. “He enjoyed taking students all over the island to look at specific spots in and out of Acadia National Park that were completely unique. From the peat bogs to the alpine ecology on certain peaks, to recreating observational studies that were done years earlier at Bass Harbor Head Light. He could take a student who hated science as a teen and ignite something in them that led them to careers in science.”

“Teaching doesn’t quite pay the bills, so Scott was also a carpenter, working with a variety of contractors on the island,” Anne said. “It’s always easier to build a new house, but Scott really liked doing the hard stuff of figuring out how to replace a rotten sill on an 200+ year old farm house. It let him see the craftmanship of those original builders, and the cleverness they had. This led him to connections with some truly memorable people.”

Those memorable people became friends.

“Lifelong island residents who could tell stories about working at the cannery in Bass Harbor, or the way they got around the lack of supplies during wars and winters. He loved stories about the herring fisheries and hauls that could make a family’s fortune,” Anne said. “Scott innately knew that a classical education wasn’t always a measure of intelligence, and thus he learned so much from so many old school Mainers. A favorite story was when he was late to re-shingle a summer cottage, and there were a group of scientists from the Max Planck institute who decided to start … and they were putting the shingles on upside down. Scott and Lyford Stanley just watched for a bit and then had to slowly explain to them why it was wrong.”

The Kisma Preserve called Scott one of the precious few real ones.

“The world and this area just lost a brilliant mind and special person who dedicated his life and career to Wildlife Education and the environment,” the preserve posted.

“As a teacher, Scott was great at working with students of varying abilities. He figured that everyone was motivated by interest, and when you found out what was interesting, you just did that thing,” Anne said. “He never met a person that didn’t teach him something or that wasn’t fascinating in some way or another.”

He was a friend to the lost, just as Gerard said, but it was more than that, too; Scott was a friend to everyone. He would lend a hand. He would lend time. He would lend a car. He would give a ride. He couldn’t say no, Anne said. He’d harvest chicken, dog sit.

“He wanted to be of service in whatever way he could. He felt for students who moved here for college, but couldn’t quite make it financially, often offering them jobs that taught them skills, and helped them stay in school. Likewise, he was the recipient of others who were willing to lend him a hand or a ride or advice,” Anne said.

In 2012, Scott suffered a cardiac event on Acadia’s North Bubble Mountain while bringing students on a research trip. Those students saved him, performing CPR. He was conscious again by the time the rangers and rescue personnel arrived.

This friend to the lost was one of the precious real ones. He was a maker of friendships, a doer of good, a keeper of joy.

“It was kind of his gift to meet people where they were, and to let them find their way. He started working at the Oceanarium and Education Center as an educator and collection overseer, which gave him a great deal of joy. He loved watching the Oceanarium come to life and talk about the history and the uniqueness of the area. Helping to recreate it into an up and coming educational resource brought him such pride,” Anne said.

“Scott was a remarkable teacher whose infectious curiosity, playful approach, and welcoming nature made a deep, positive impact on generations of College of the Atlantic students. He will be sorely missed,” COA’s Rob Levin said, Thursday.

He is survived by his children, who Anne said, fascinated him every single day: Samuel, Maxwell, and Thistle.

“They were (and probably still are) a constant form of wonder and amazement for him. Also Noah—a bonus kid—another source of wonder and entertainment,” Anne said.

He also left behind his siblings Karen (Doug) of NYC, Rick (Carlyn) of Seattle WA, and Don (Phi) of Tucson. And his former wife, Anne.

Also missing him is his constant support crews: Matt Gerald, Matt Drennan, Matt Haviland, Jamie Lewis, Dave Folger, Scott’s housemates—Molly and Tommy, and a slew of past and present students and colleagues. Scott was predeceased by his parents, Robert and Joan, both middle school teachers who begat several generations of educators.

Anne sent extra love and admiration for Matt Gerald, who she said “has been so incredibly helpful and wise as we all have navigated Scotty’s death and all the crazy stuff that went with it. So much love and laughter in the past several weeks.”

A memorial celebration is planned for the first weekend in October at COA. More information about that, and a fund in his name will be made later in the summer.

Scott loved a good story and enjoyed telling him – true or not. Anne said that she would love to gather stories and pictures for his family.

Please feel free to submit any to scottstories64@gmail.com

Update. On May 10 at 3:15 p.m., we tweaked one word in one quote for clarity.

Follow us on Facebook. And as a reminder, you can easily view all our past stories and press releases here.

If you’d like to donate to help support us, you can, but no pressure! Just click here (about how you can give) or here (a direct link), which is the same as the button below.

If you’d like to sponsor the Bar Harbor Story, you can! Learn more here.

we joked so many times about the 'dead of the week' I can hear Scott laughing that he made the cut big time. from croquet to gardens and from raising sheep to clearing spruce we did a lot together. hamba kahle Scott. I'll think of you out by the big erratic in the woods, or hauling loads up the hill, running across the bay in all kinds of weather, comparing gardens and making plans.

One late August on Gotts we stopped Scott on his way up the hill to lunch, to ask if he’d seen the boys (his and ours) who’d been wandering around the island since breakfast. Not one to be worried about free range 10 year olds, he said he’d seen them by “the Gut” a few hours before having “a perfect Robert McClosky sort of day”. We will miss Scott dearly.