The Bar Harbor Story is generously sponsored by Paradis Ace Hardware.

OTTER CREEK—Otter Creek isn’t a community that gives up easily. That’s true when it comes to its livelihoods, its community, and its waterfront. And just because that working waterfront is pretty much gone doesn’t mean that people of Otter Creek don’t want it back.

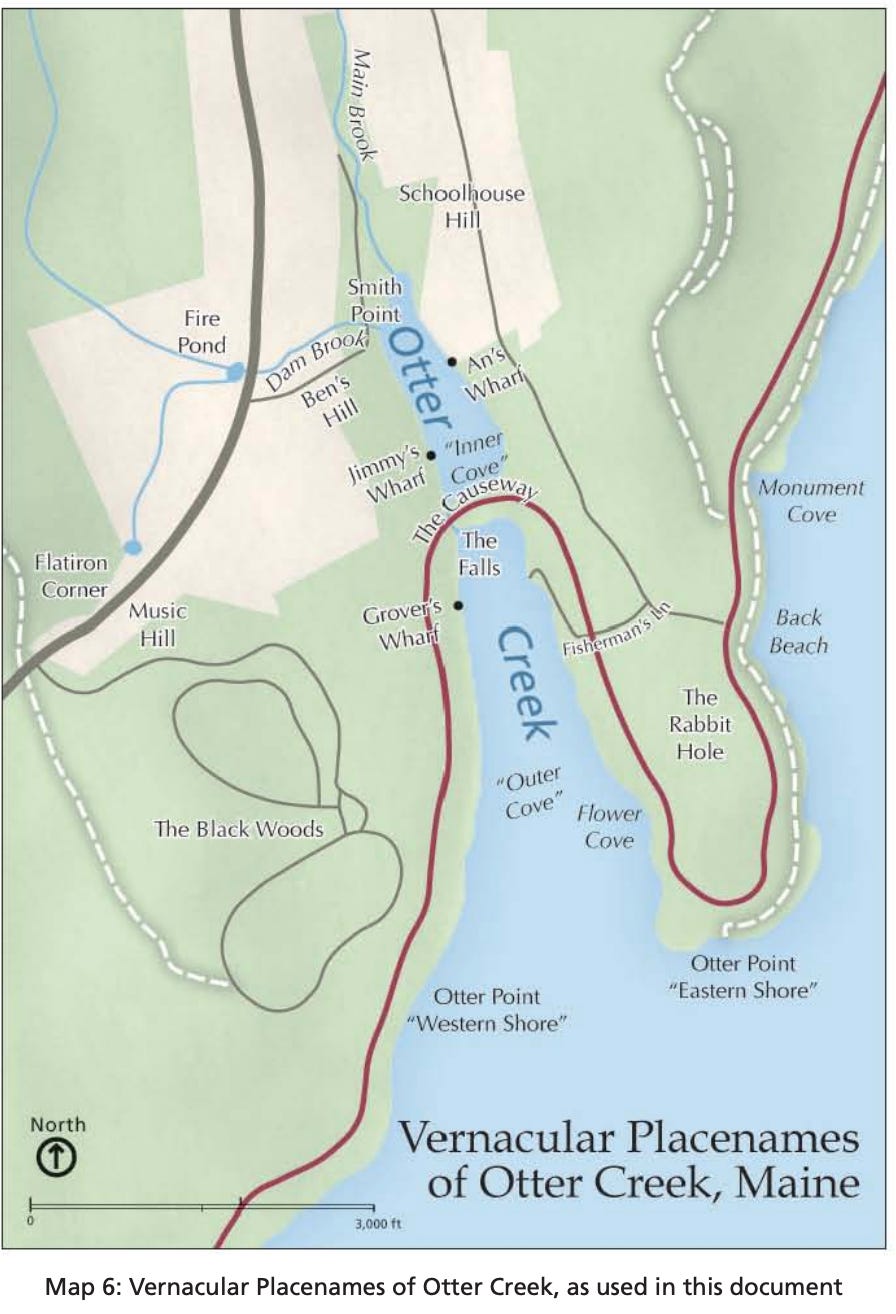

What complicates matters is just how to return that waterfront when the village is surrounded by Acadia National Park, where even the land adjacent to its narrow boat launch is owned by the park and when a causeway originally built to create a swimming pool for the park has cut the town’s access to the ocean, and when it might require an act of Congress just to get a tiny bit of land back.

“Most of your problems are caused by the Goliath around you,” Mount Desert Town Manager Durlin Lunt told members of the Otter Creek Aid Society at its July 31 meeting.

Lunt didn’t grow up in the Village of Otter Creek, but in another part of the Town of Mount Desert, a town that’s just over 2,100 strong, but he loves it, he said. He loves visiting. He loves the people of the village. He wants them taken care of.

“I’m always delighted to come over to Otter Creek because there is really a real community feel over here,” he said.

Lunt has joined forces with Steve Smith who has battled the park on multiple issues for years. Most of those issues involve fishing and Otter Creek, but include a 1987 protest with Bucksport’s Mike Tait over the park’s entrance fees at Sand Beach.

Smith is the great, great, great grandson of early settler Louisa Smith. In a 2016 letter to the Mount Desert Islander, he wrote, “It’s bad enough that our local culture here in the Creek has been adulterated almost beyond repair over the years.” He called the inner harbor in Otter Creek an “ecological disaster.”

The men were in high school together on the island. They have, like many others at the society meeting, a mission: to restore Otter Creek’s working waterfront.

To do that they have to deal with the federal government.

“What we are asking for is really quite reasonable,” Lunt said.

The problem is how to get those asks, to restore the waterfront, to reinforce the community.

“People like Steve and I aren’t going to be here to see this finished,” Lunt told those gathered. It’s going to eventually be up to others to get Otter Creek’s working waterfront back. And he started naming them—the people who might pick up the gauntlet in the quest to get Otter Creek’s working waterfront.

“Wishing to create a showpiece swimming pond for the new national park, Rockefeller enclosed Otter Creek’s inner cove in a scenic causeway, and worked to extinguish the waterfront access of the community while making informal agreements to allow Otter Creekers continued access to their fish houses on the outer cove beyond the newly constructed shoreline drive,” Dr. Douglas Deur wrote in The Waterfront of Otter Creek, an enthnographic report that involved the National Park Service in 2012. “By 1940, much of Rockefeller’s vision for Otter Creek’s waterfront—except the swimming pond—had been achieved, and over time Rockefeller transferred his lands to the National Park Service for incorporation into Acadia National Park.”

HOW DO YOU RESTORE A WORKING WATERFRONT?

For Lunt there are currently five main points to restore Otter Creek’s working waterfront. They involve the tidal flushing of the inner harbor, getting land from Acadia National Park to make the village’s boat launch ramp a bit more usable, clearing the vista so that people can see the harbor again, restoring the traditional trails that were there before Rockefeller acquired the land, and determining the ownership of Quarry Path, another name for the Park Loop Road causeway.

“It’s time we brought the hammer down.” Smith said that they’ve gotten nowhere trying to work with the park commission. ”Years and years and years are going by.”

It’s a lot of fight for an aid society that has shrinking coffers and just around $450 a year for income. Its biggest expenses are insurance, which is mostly liability on the fish house and $5,000 in fuel oil each year.

“It’s killing us,” said John Macauley who has been serving as the society’s president and on the Mount Desert Selectboard. “It’s a downward spiral.”

He recommended shutting down the hall for the winter. Everyone agreed.

It might be a lot of fight for Lunt and Smith, too, but they aren’t stopping, they say.

A big piece of the problem is that how do you defend and enhance a working community where the people are busy working?

You keep at it. Lunt and Smith have been attending the quarterly Acadia National Park Advisory Commission meetings, bringing up Otter Creek’s needs over and over again.

“I’m sure when I go through the door, they’d rather see the devil himself coming through there,” Lunt said.

THE OBSTRUCTIONS

At face value, a tiny bit of land for a boat launch seems an easy ask and it’s one that Lunt has been hammering away at.

The amount of land requested is basically 55 feet by 55 feet. It’s .052 of a football field, including the end zone. It’s .63 of an NBA basketball court.

The land is adjacent to the boat launch on Grover Avenue in Otter Creek. The town wants it for the purpose of expanding vehicular access to the municipal facility.

In early June, the Acadia National Park Advisory Commission did not honor a request from the town of Mount Desert for a 3,000-square feet piece of land owned by Acadia National Park in the village of Otter Creek without an encumbrance of land, commonly called a land swap.

Lunt made the original request in February. A subcommittee of the Commission, led by Darron Collins, former president of the College of the Atlantic, met in March via Zoom, and Collins announced on Monday, June 3, that the subcommittee decided that any request must occur via a land swap. This typically occurs via an act of Congress. The Commission advised Lunt to have the town make a request of its federal representatives.

The park has no authority to simply give away land, Collins said. National park lands are of national interest and any expansion should be part of a land swap unanimously approved, most of the other Commissioners agreed.

Lunt said he didn’t believe in the “slippery slope theory" about why the land should not be given to Otter Creek.

The boundary legislation was designed to protect MDI towns from further land incursions, he said, but now it “has been weaponized by ANP administrations to protect the park from carrying out its obligations to preserve and protect the cultural heritage of Otter Creek.”

“That boundary legislation,” he said, “can be amended to allow a land transfer for enhanced vehicular access to the Otter Creek launching facility without triggering the "slippery slope" of mass transfers of land from the NPS. The U.S. Constitution (a most revered document) has been amended twenty-six times. Surely, the boundary legislation can be amended once.”

On Wednesday, he said that the legislation had been weaponized to protect the park, something he understands, but he rebukes the park’s slippery slope argument as one that most governments use to keep from action, firmly believing that the park shouldn’t need to get a federal act of Congress to move a shovel full of dirt or to give a village a little bit of its land back.

“We can do it in a way that would protect and not create destruction,” he said.

THE VILLAGE OF OTTER CREEK

Part of the problem is that the Village of Otter Creek isn’t as well known as other parts of Mount Desert Island or the Maine coast.

Sam Belknap of the Island Institute told the people gathered at the Otter Creek Aid Society’s Annual meeting, “I did not actually know (Otter Creek) existed on this corner of MDI.”

They didn’t seem to hold it against him.

“You’re damn well not alone,” one woman muttered.

“Our waterfronts often have deep roots and important stories to tell,” according to the National Working Waterfront Foundation. The telling it is a large part of the battle. It’s hard to make people care about something that they don’t know about.

Otter Creek has been trying to get people to know about it for decades.

HOW DID OTTER CREEK LOSE ITS WORKING WATERFRONT?

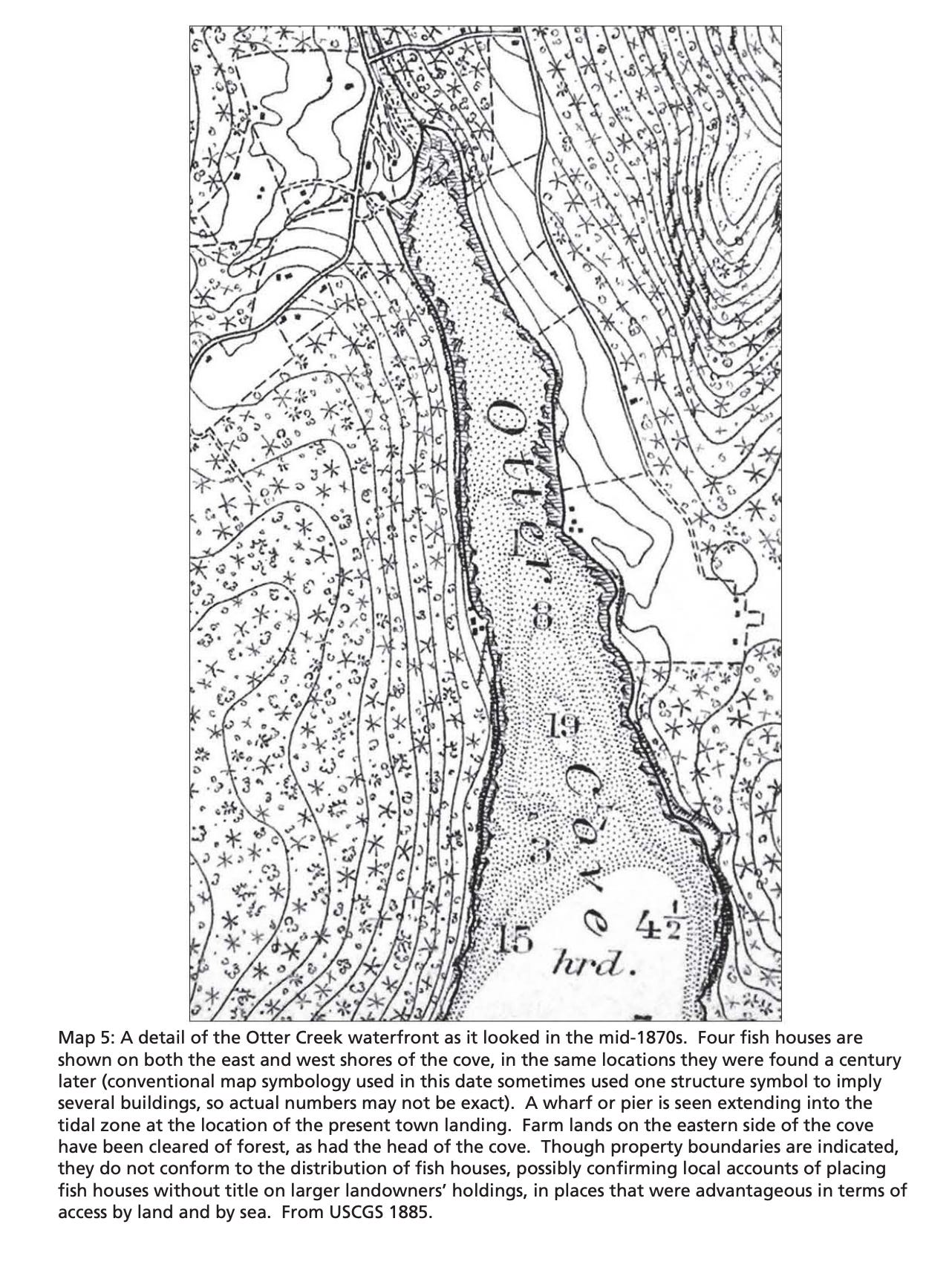

There were multiple steps along the way that impacted Otter Creek’s working waterfront where fishing houses dotted the shores.

Back in 1936, Mount Desert’s Warrant Committee voted to indefinitely postpone Article 33 at town meeting. That article said that the town would discontinue the use of the town way and town landing to Otter Creek. The vote came at the height of the Great Depression.

“Work was hard and times were tough,” Lunt said in February.

A lot of people at that 1936 meeting, he said, were under the employ of John D. Rockefeller. Rockefeller wanted the waterfront to be part of the park. He also wanted the cove to be a swimming area.

The land was given. The causeway was built.

Lunt said that the current access to Otter Creek Harbor has limitations and the harbor itself is dry at low tide, but before that land acquisition, it had an active quarry, schooners, fishing, and was a working waterfront. It still has one or two fishermen.

If government agencies could cooperate and allow for the Seawall Road to be fixed, Lunt wondered, why couldn’t something similar happen in Otter Creek.

Seawall Road is state-owned and runs through and to the federal government’s national park and services the towns of Southwest Harbor and Tremont. After months of being closed, the state government allowed local contractors to have a temporary fix so the road can be open this summer. The federal government also granted the right to repair it.

To many, Otter Creek’s problems aren’t quite as visible as a road broken, pavement upheaved by the storm surge, but to some, it’s even more visually obvious and is symbolized in the 1938 causeway that makes the village landlocked.

“The relationship between Otter Creek and the National Park Service had never been an easy one. Otter Creek was the only town to be fully encircled by the new park, and to effectively lose access to a working waterfront in the process of the park’s creation,” Deur wrote.

“These developments compounded the many other challenges facing fisherman on this cove in the mid-20th century. Some of these were of longstanding duration, such as the cove’s exposure to waves and the ill effects of bad weather, but others arose from newer economic conditions such as changing fish stocks and markets, and the industry’s transition to larger boats and power-assisted technology,” Deur wrote. “The few people who held on to the traditional fishing lifestyle did so with great effort, and often out of great affection for their heritage and for the traditions of small scale Maine fishermen. By mid-century, only a very small community of fishermen remained, launching their boats from small waterfront fish houses on remnant inholdings. At certain times, park staff demolished fish houses, abandoned and sometimes not, as park management prioritized natural resources and landscapes rather than cultural resources and landscapes in this portion of the park.”

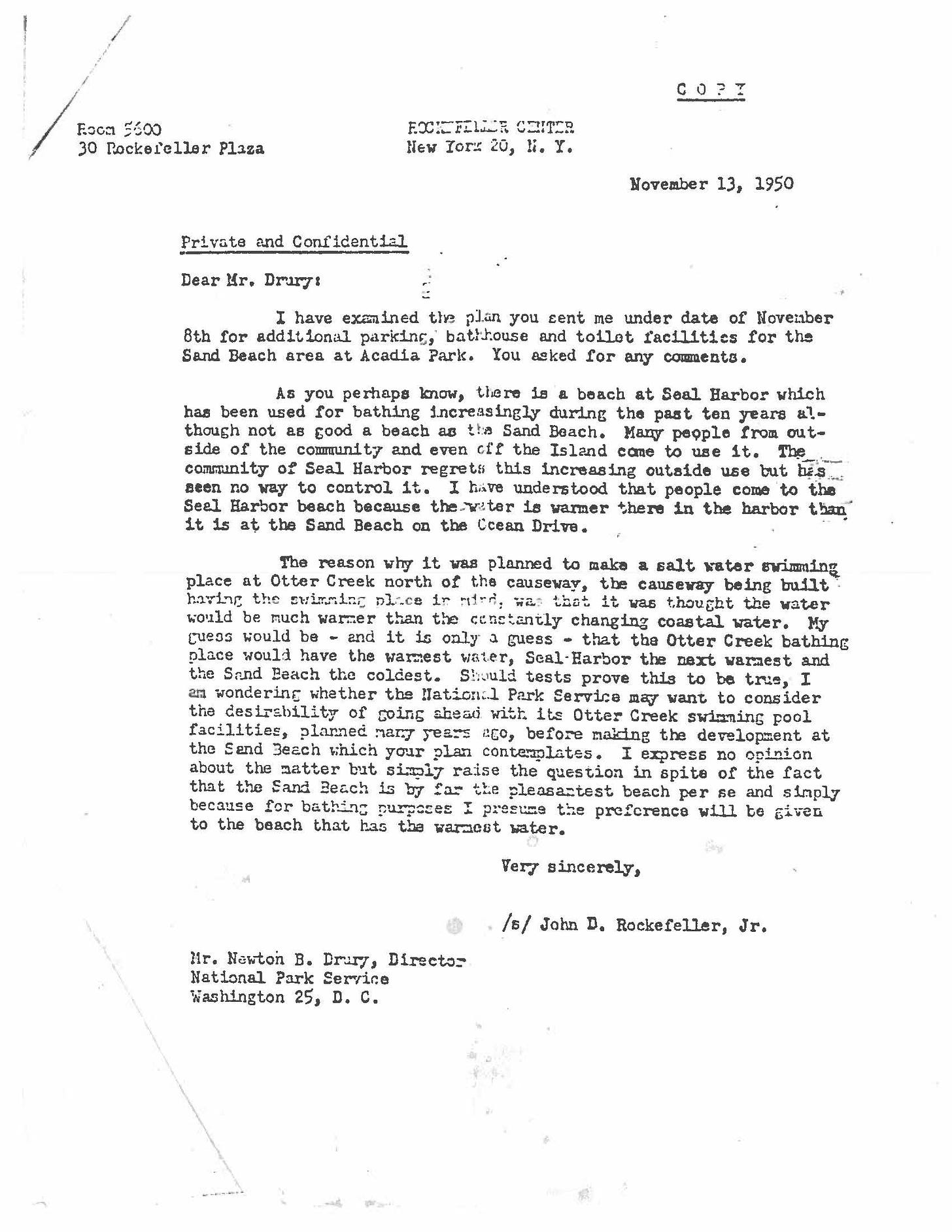

THE ROCKEFELLER LETTER

The 1950 letter from John D. Rockefeller to NPS National Park Service Director Newton B. Drury illustrates the time directly after the acquisition.

“As you perhaps know,” Rockefeller writes, “there is a beach at Seal Harbor which has been used for bathing increasingly during the past ten years although not as good a beach as the Sand Beach. Many people from outside of the community and even off the island come to use it. The community of Seal Harbor regrets this increasing outside use but has seen no way to control it.”

The water there, he explains, is warmer than Sand Beach. Therefore, Rockefeller posited, maybe they should do their plans for the causeway construction to make that salt water swimming hole there rather than further developing Sand Beach at that time.

“The gulf between the experiences and worldview of the park’s affluent boosters and the residents of this modest town were vast indeed—that Rockefeller and his fellow park supporters may not have recognized the Otter Creek waterfront as a legitimate asset is perhaps not completely surprising, in light of the paucity of buildings, the ambiguity of certain fishermen’s titles to the land, and a variety of other idiosyncrasies. Nonetheless, as residents attest, the community experienced impacts from park creation that are arguably unique, and have contributed to changes within the community of Otter Creek that are still playing out today,” Deur wrote.

There are lasting impacts from decisions that happen across history and in present times. Lunt, a student of history who quotes with great facility the political giants, philosophers, and songwriters of the last few centuries, knows that. Smith, a man who lives history with his arguments against the federal government, knows it, too.

Everyone pretty much knew everyone at the meeting of the Otter Creek Aid Society. Many wore their passions on their sleeves.

“It’s about money,” Reed Miller said from a folding metal chair in the back row of the hall. He wanted to get out the word, make TikTok reels and YouTube videos. No more PowerPoint presentations, he suggested.

“There was really no compelling reason” for federal control of the harbor, Lunt said. “They didn’t want the local people at Seal Harbor Beach.”

Local people, though, are what makes up a community, what holds it together, and what fights for it.

“Our waterfronts often have deep roots and important stories to tell,” according to the National Working Waterfront Foundation.

Telling it is a large part of the battle. It’s hard to make people care about something that they don’t know about, but it’s a battle that many in Otter Creek think is more than worth it.

This is just one in what we think is likely to be a long series of Otter Creek. To find other stories, search for “Otter Creek” in the archive.

On Monday, August 5, Lunt will give the Mount Desert Selectboard a report about his presentation to the society. That meeting is at the town hall meeting room in Northeast Harbor at 6:30 p.m.

It is also via Zoom

Meeting ID: 248 566 175 Password: 919872

LINKS TO LEARN MORE

The Waterfront of Otter Creek, a Community History

If you’d like to donate to help support us, you can, but no pressure! Just click here.

If you’d like to sponsor the Bar Harbor Story, you can! Learn more here.