Hospital OB Nurses Rally Community & Urge People to Sign Petition To Keep Maternity Wing Open

The Bar Harbor Story is generously sponsored by Swan Agency Real Estate.

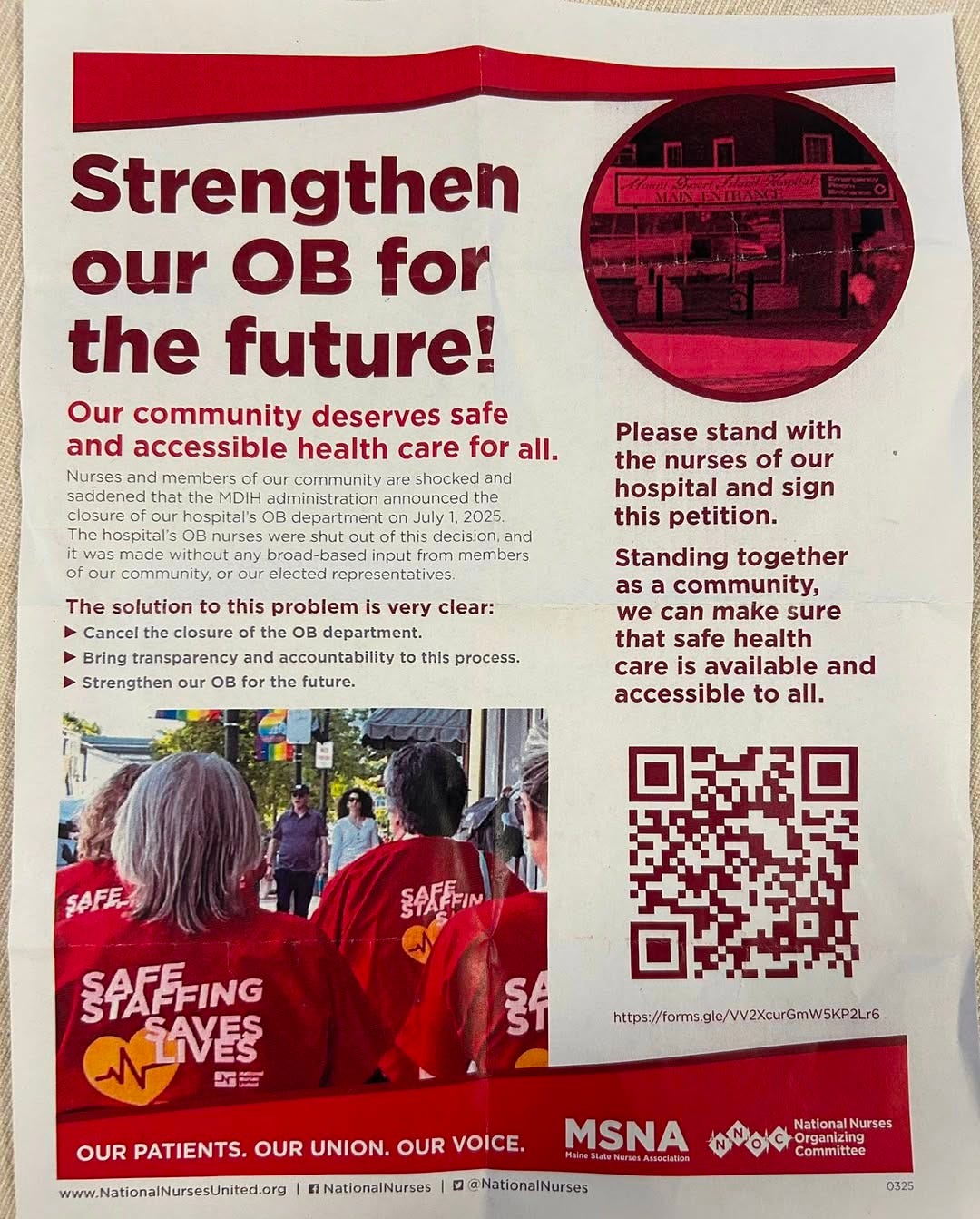

BAR HARBOR—Local nurses are urging community members to sign a letter detailing three elements to strengthen the hospital’s obstetrics department rather than closing it, July 1.

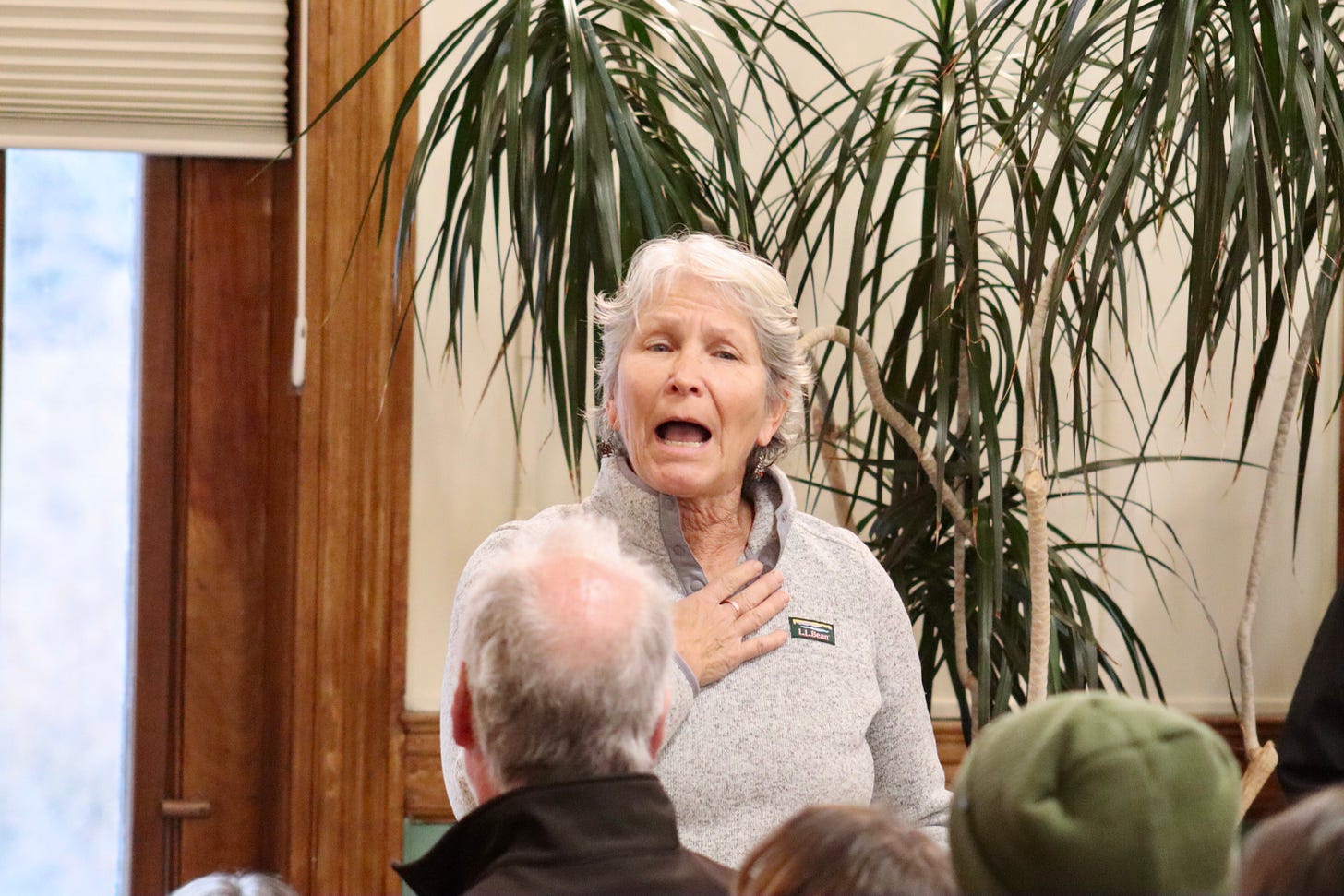

Well over 100 members of the Mount Desert Island community gathered with local nurses, Sunday afternoon, to discuss Mount Desert Island Hospital’s March 27 announcement that it is closing its birthing center, July 1.

“The people in our community deserve care regardless of how it lines the hospital’s pockets,” Micala Delepierre said before she asked the nurses sitting at a table at the front of the crowd how to support them.

The hospital has stated that the closure is not a financial decision.

Janice Horton, RN, a 32-year veteran of MDIH’s OB department invited everyone to sign a resolution that requests the hospital to cancel the planned July closure of its birthing unit, establish a community task force to advise the hospital’s administration, and “bring transparency and accountability to decisions that are being made about the OB department.”

Members of the Mount Desert Island community sat on floors, chairs, and piano benches. Many stood at the back of the room. They applauded each other’s comments multiple times. Some cried.

“It’s a job I truly love,” Horton said during the discussion that lasted for just over an hour and she added that the birthing unit at Mount Desert Island Hospital is “a place I love to be.”

Audience member after audience member echoed her love. They and the nurses told stories of milkshakes and quilts, kindness and support, of babies born. Multiple pregnant women and new babies attended.

Now, after the hospital’s announcement last week, many community members and nurses have said that they are reeling, trying to imagine a thriving island community without a maternity unit.

“Instead of becoming a service; it became a business,” Dr. Mary Dudzik said of the healthcare industry. That sickens her, she said. “Why is it always women and children’s services that go—whoop—out the door?”

Dr. Dudzik said that she can’t wrap her head around a $37 million expansion instead of funding OB.

“It’s not right. It’s not right,” another woman called out in support.

"There is no place like the MDI OB Department,” Dr. Dudzik said.

The hospital has said in prior releases that the Kogod Center for Medical Education was an entirely donor-funded project. Acadia Family Center gifted a Southwest Harbor building to the hospital. On the hospital’s Labor and Delivery Closure FAQ page, it states that the hospital’s "planned renovation is funded by grants and gifts specifically designated for capital improvements including the expansion of the emergency department. These dollars can’t be used for operating costs like staffing or running the labor and delivery unit."

Others attending wondered if the hospital could potentially raise dedicated funds and an endowment to support the OB unit and its staff.

Fulbright grantee, author, and retired nurse midwife Linda Robinson said that choices to close down rural maternity rooms throughout the country had to be framed as a human rights abuse.

“I never felt like I was going to work. I felt like I was going to my other home,” she said of her time working with the hospital’s OB unit. “I was so proud of the care we gave.”

Doula Sarah Tewhey spoke similarly. She told the crowd that she heard the news of the closure while she was driving to Augusta to work on doula issues at the state house. She’s the chair of the Maine Doula Commission (MDC). A doula is a person who is trained to support women in emotional and physical ways during, before, and after childbirth and pregnancy.

According to its website, the commission’s purpose is “to expand access to doula services by reducing financial, logistic and cultural barriers to pregnant people in Maine. MDC recognizes the vital impact of doulas in improving both the experience of pregnant people and Maine’s perinatal health outcomes. We seek to foster a strong, culturally competent doula workforce through community building, education, legislation, and public health outreach.”

When Tewhey heard the news, she was about 30 minutes from Augusta. She pulled the car over and cried.

“I had the remainder of the drive to get mad,” she said.

Tewhey said she hears from her clients of MDI Hospital that they didn’t know birth could be like they are at the hospital. The community, she said, has something special in a state that’s already lost one-third of its birthing units because of expenses, lowering birthrates throughout the state—not just Mount Desert Island—and low reimbursement rates from Medicare.

Hospitals and hospital systems can’t solve this problem, nor can the state and the state’s department of human services, she said.

“The OB nurses are special” at the island hospital, she said, characterizing them as kind, trauma-informed, and focused on individualized patient care.

“This is where we are in Maine,” she said. “It makes me want to scream that this is our best solution.”

She also referenced the Waldo, Maine hospital’s closure of its birthing unit, which will occur in April. The hospital first told the community of the possibility of closure and issues in June 2024, and held a forum in August. The closure was announced in November – five months later.

That, she said, isn’t what’s occurring in Bar Harbor.

“This community deserves better,” she said. “I’m a doula. It’s my job to speak up and advocate.”

People stood to applaud her comments.

While the hospital has said it will still have emergency maternity services available in its emergency department, Southwest Harbor resident, Carly Thaggard, explained that there’s a difference in a birthing experience when people have maternity staff and their OB doctor that they have had prenatal care with.

She should know, she said. Her second child was trying to be born during a frantic ride from Southwest Harbor to Mount Desert Island Hospital.

“I cannot tell you the relief that I had and the care that I felt instantly,” she said when she saw her OB doctor and the maternity nurses who came into the emergency room after she’d arrived.

“They felt like my protectors,” she said. “Their expertise was very important.”

She was in labor. She was screaming, which worried the ER staff who, she said, had a spotlight and other extra equipment there.

“Yes, it’s screaming, but it’s a different kind of screaming,” she said the maternity professionals told the others. They removed the spotlight. The OB nurses and doctor knew what her screams meant.

There’s a difference between having a staff specially trained in maternity and a staff trained for emergencies, Thaggard said. “There’s that technical piece.”

Shannon Murray, a nurse anesthetist at Mount Desert Island Hospital, questioned the nurses about the safety of the department given the volume of births. She also asked how many units of blood were in the hospital, which was unanswered.

Her statements echoed the hospital’s first paragraph on its fact page, which states, “MDI Hospital is closing its inpatient labor and delivery unit due to a significant decline in births, increasing financial pressures, and the challenge of maintaining specialized staff for such low-volume care. Only nine babies have been born at MDI Hospital this year. In 2024, only 33 babies were delivered, down from more than 100 just a decade ago. Critically, with so few births, our nurses and providers cannot maintain the necessary skills and experience required for safe deliveries. Patient safety is our top concern, and ensuring that our staff can provide the highest level of care means making this difficult decision.”

Kate Cough had also asked the nurses about the difficulty of keeping up skills when the hospital had 32 births last year and nine so far this year.

The nurses said that there’s a lot of work being done on the state level about keeping nurses ready to recognize and respond to obstetrical emergencies. There is also new technology to help with that, ways to run simulations on different birthing complications and scenarios, she said and outside personnel to evaluate the process and OB staff response to those simulations.

Keeping skills despite lowering birth rates is a concern for rural departments throughout the state, the nurses said, but it’s also something the state is working on. Some Maine nurses temporarily rotate out of their rural hospital in order to keep up their skills and temporarily rotate into places like Northern Light Hospital in Bangor, which delivers approximately 164 babies a month.

Staffing was brought up in a Mount Desert Islander article about the closure. Zach Lanning wrote, “The dwindling number of births also made it difficult to recruit new staff, according to the hospital. And existing providers — who are required to deliver a certain number of babies or perform a certain number of specialized procedures like a cesarean section to maintain their license — were left to divvy up a dwindling pie.”

Nurses said that if there were not enough staff available to safely birth a child at the hospital, they would divert the mother and baby to another hospital. Similarly, when there is a potentially catastrophic crisis, mothers have been sent via LifeFlight to hospitals in Bangor, Portland, and Boston.

The hospital has said in its press release that it intends to:

“Double the size of the emergency department through a grant and donor-funded renovation. One of the new rooms will be equipped with labor and delivery equipment for emergency births.

“Continue coordinating with nearby facilities to ensure smooth transfers for deliveries.

“Have MDI Hospital’s emergency care staff rotate through partner hospitals to maintain their labor and delivery skills.

“Explore a women’s health patient navigator program to guide expectant mothers through prenatal, delivery, and postpartum care—offering personalized support and care coordination.”

THE COMMUNITY IMPACT

One woman in the audience said that the hospital is cutting off the supply of children when the town is building a new multimillion dollar school. She also criticized the building of the new Kogod Medical Center meant to provide housing for visiting medical students and others interested in learning about rural healthcare.

Others criticized the hospital for not involving the community in the decision or allowing community members to play a part in trying to find solutions while simultaneously expanding with a new emergency room and entrance.

Bar Harbor Town Council Vice Chair Maya Caines attended, but did not speak. Rep Holly Eaton (D-Deer Isle) and Rep Gary Friedmann (D-Bar Harbor) and Senator Nicole Grohoski (D-Ellsworth) all spoke of hearing news of the closure on Thursday.

“My first thought was I’ve given birth to two children,” Rep. Eaton said. Each time she had to drive from Deer Isle to Ellsworth, which she called a pretty straight shot. Still, she said, “every single mile that I travelled felt like 100 miles.”

Rep. Friedmann referenced the town’s rebuild of the Conners Emerson School, “We’re putting $60 million dollars into a new elementary school and you’re telling me we can’t figure out how to keep a birthing center open?”

According to a February 2024 white paper by Hailey Bondman and Alexandra Zimmerman, “A majority of rural births occur at local facilities, yet more than half of rural counties no longer have access to obstetric (OB) services. Studies show a doubling of infant mortality rates where counties have lost OB services. Additionally, out-of-hospital births and preterm births increase in counties without hospital-based OB services. Recent changes in the maternal health landscape have the potential to exacerbate the preexisting disparities in rural maternal health related to the availability of the maternal health workforce, maternity care coverage policies, and the provision of equitable access to maternal care services.”

COMPLEXITY

Some community members remained hopeful that there could be a solution despite the complexities of the healthcare system for Maine hospitals and particularly critical access hospitals like the one in Bar Harbor.

“Now’s your opportunity to be in the process,” Senator Grohoski said. It’s not clear that there is necessarily a legislative solution, she said, but the three legislators are aware of the “crumbling” healthcare situation in the state. “We are in a crisis, a breaking point and continuing business as usual is not working.”

There will be fewer than 20 birthing units open in the entire state after this summer. Eight have closed in the past ten years, including Blue Hill Memorial Hospital. There is still an option to have a hospital birth at Northern Light Maine Coast Memorial Hospital, but for emergency situations, seamless prenatal and post natal care, that worried Emily Wright, RN, and primary obstetric nurse, and others.

According to the American Legal Journal, “Maternity wing closures also create several pressing health equity concerns. Many women who are giving birth have no choice but drive more than 40 minutes to get to maternity care due to the shortage of providers and facilities. Some pregnant women are temporarily moving to be closer to the maternity provider. Temporary relocation is something that not everyone can afford. Geographic isolation from comprehensive health care increases the risk for complications and death. Many low-income women who are pregnant do not have the financial or reliable resources to travel long distances.”

The hospital’s release stated of its CEO and President Christina Maguire that she “emphasized that the closure does not reflect a diminished commitment to maternal health. Instead, it reflects harsh realities: skyrocketing costs, a shrinking rural population, and inadequate reimbursement from federal and state sources.”

The hospital later said those skyrocketing costs refer to the increased cost of living and basic necessities.

Many of those attending spoke to the complexity of the situation and the multiple obstacles toward keeping a maternity unit open in a rural area when there are lowering birthing rates, reimbursement issues, and other difficulties.

But, they stressed that they wanted to keep the department open and be involved in a process that’s open and transparent, saying that now is the time to look for solutions, not just on the local level but on the state and national levels.

“Closure is not going to solve that,” Ellen DaCorte, senior charge nurse/OB nursery at the hospital. She’s been a hospital employee since 1995 and an OB nurse for more than 25 years.

A theme often brought up was that the nurses were grateful for each other’s support and the community’s.

DaCorte invited everyone to attend the hospital-sponsored meeting at the Jesup Memorial Library on Thursday, April 3, and to sign the petition mentioned by Horton. But before that? The nurses wanted to thank everyone for caring, for attending, and for their support. To do that, they handed out little milkshakes, the same drink they give women after they’ve brought their babies into the world.

“We take joy in making these milkshakes, especially right after birth. We believe it offers the perfect burst of energy,” DaCorte said.

It was “a gift of energy and love from us, your nurses,” she said, “and we truly care.”

The community stood up to applaud their nurses, too, many shouting that they care about them: nurses who have birthed a community in more ways than one.

LINKS TO LEARN MORE

Town Hall forum on Thursday, April 3, at the Jesup Memorial Library from 4-5 p.m

Direct link to view and/or sign the petition

Photos: Shaun Farrar/Bar Harbor Story

Follow us on Facebook. And as a reminder, you can easily view all our past stories and press releases here.

If you’d like to donate to help support us, you can, but no pressure! Just click here (about how you can give) or here (a direct link), which is the same as the button below.

If you’d like to sponsor the Bar Harbor Story, you can! Learn more here.

The MDI hospital board is made up of members who doubtless voice support for keeping the island towns as vibrant, year-round communities. Yet in this hypocritical decision to close the maternity ward they have dome as much to hurt that effort as the most rapacious developer turning year-round housing into seasonal, tourist housing.

Why not have 2 or 3 of the doctors train in OB - hasn’t Dr Hanke delivered babies? Then have may be 6 med surg nurses train for OB. As they won’t get much practice in BH why not share with Ellsworth. Or request an opportunity to do “refresher” days up in Bangor a few times a year?

I’m sure there are other ideas. MDIH serves this whole island and although it’s hard to find anywhere to live in BH these days, there are lots of people living on the rest of the island - even Trenton.

It’s really upsetting to lose that special place to have a baby.